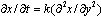

"In scientific thought we adopt the simplest theory which will explain all the facts under consideration and enable us to predict new facts of the same kind. The catch in this criterion lies in the word 'simplest'. It is really an aesthetic canon such as we find implicit in our criticisms of poetry or painting. The layman finds such a law as  less simple than 'it oozes', of which it is the mathematical statement. The physicist reverses this judgment, and his statement is certainly the more fruitful of the two, so far as prediction is concerned."

less simple than 'it oozes', of which it is the mathematical statement. The physicist reverses this judgment, and his statement is certainly the more fruitful of the two, so far as prediction is concerned."

- Haldane, 1985

Course Meeting Times

Lectures: 3 sessions / week, 1 hour / session

Recitations: 2 sessions / week, 1 hour / session

Subject Contents

In this subject, we consider two basic topics in cellular biophysics, posed here as questions:

- Which molecules are transported across cellular membranes, and what are the mechanisms of transport? How do cells maintain their compositions, volume, and membrane potential?

- How are potentials generated across the membranes of cells? What do these potentials do?

Although the questions posed are fundamentally biological questions, the methods for answering these questions are inherently multidisciplinary. For example, to understand the mechanism of transport of molecules across cellular membranes, it is essential to understand both the structure of membranes and the principles of mass transport through membranes. Since the transported matter may combine chemically with membrane-spanning macromolecules and/or carry an electrical charge, it is essential to understand the principles of chemical kinetics and of transport of charged molecules in an electric field.

Knowledge of transport through membranes is based on measurements. These measurements lead to physically and chemically based mathematical models that are used to test concepts based on measurements. The role of mathematical models is to express concepts precisely enough that precise conclusions can be drawn (see quote by Haldane, above). In connection with all the topics covered, we will consider both theory and experiment. For the student, the educational value of examining the interplay between theory and experiment transcends the value of the specific knowledge gained in the subject matter.

Teaching Methods

Several kinds of activities are provided to help the learning process.

- Three lectures each week to introduce new material.

- Two recitations each week to review material, solve problems, and answer questions.

- Two projects - one experimental and the other theoretical - to help students learn to pose testable hypotheses, to conduct research, and to communicate results.

- Weekly homework assignments to encourage students to actively assimilate the course material.

- Two evening examinations and one final examination to provide an occasion to integrate the subject material and to obtain an objective evaluation of the student's understanding of the material.

Homework

Weekly homework assignments provide an opportunity to develop intuition for new concepts by actively applying the new concepts to solve problems and answer questions. The process of actively struggling with the use of new ideas until you understand them is an effective and rewarding form of education.

Weekly homework assignments will typically be due exactly one week after being issued, in recitation. Late homework will not be accepted. Homework assignments will be corrected, graded, and returned the week after they are due. Solutions to the homework will be distributed with the corrected homework.

Homework problems will be chosen for their educational value. Some of our best problems were assigned in previous years, and it is a relatively easy matter to acquire solutions. If you skip the process of personally struggling with the use of new concepts, you will have destroyed your most important educational experience. Reading someone's solution to a problem is not educationally equivalent to generating your own solution. We encourage students to work together to understand the concepts in the homework. However, each student should work out his/her own solutions. Submitted homework should reflect the knowledge of the individual. If you work with other students (living students or the written testaments of previous students), please include their names on your homework sets.

It is generally tempting to postpone working on homework until the night before it is due. This is a poor plan because it limits your ability to interact with fellow students and the teaching staff.

Examinations

Two evening examinations will be given: one between lectures 13 and 14; and one between lectures 24 and 25. Students will have two hours to complete the exam, which will be designed as a one-hour exam. These exams are closed-book: notes on both sides of one 8 1/2 × 11 sheet of paper may be used for reference in the first examination, and notes on both sides of two 8 1/2 × 11 sheets of paper may be used for reference in the second examination.

A three-hour final examination, given during the Final Examination Period, will cover all the material in the subject, but will be weighted more heavily on material not covered in the examinations given during the term. The final examination is closed-book; notes on both sides of three 8 1/2 × 11 sheets of paper may be used for reference.

Computer-Aided Exercises

Six software packages will be used:

- The random-walk model of diffusion,

- Macroscopic diffusion processes,

- Chemically-mediated transport across membranes,

- The Hodgkin-Huxley space-clamped model for neural membranes,

- The Hodgkin-Huxley propagated action potential model, and

- Voltage-gated ion channels in membranes.

These software packages will be used in lectures, recitations, and homework. No knowledge of computers is required to perform these exercises.

This term we will use versions of each software package based on MATLAB®. Documentation is available online, and can be found in the tools section.

Projects

This subject includes two projects. The first is a laboratory project on microfluidics. It provides an opportunity to study molecular transport and diffusion. In the second project, a software representation of the Hodgkin-Huxley model for a neural membrane will be used to introduce students to the use of computer simulation to understand the behavior of complex systems.

The projects provide an opportunity to learn about:

- Planning experiments,

- Acquiring, processing, and interpreting data, and

- Communicating the results to others.

Both projects require a written proposal, which includes a well-defined hypothesis and procedures to test the hypothesis. For the laboratory project, you will use equipment in an MIT laboratory. You will have to schedule a 2-hour session to complete an introductory pre-lab exercise. You can then schedule additional time at your convenience to complete your project (typically 3-4 hours total). The theoretical project is done on a computer.

Students are encouraged to work in pairs for both projects. Partners are encouraged to submit a joint proposal, to cooperate in processing data, in discussing interpretations, and in preparing their reports. Partners are also encouraged to submit a joint report. We strongly believe that students learn more by working with other students than by working in isolation.

The report for the first project is written. It should be approximately 10 pages long and structured as a scientific paper. The report for the second project is oral. It should be 12 minutes in length and should be delivered during the next to last week of the semester.

The reports for both projects have firm due dates, which are listed in the calendar section. There is a severe lateness penalty: the grade for a late report will be multiplied by a lateness factor

L = 0:3e -t/4 + 0.7e -t/72

where t is the number of hours late.

Communications Intensive: Crafting Technical Presentations

This subject is communications intensive. We feel that communications skills are essential for professional engineers and scientists. We also feel that the process of creating written manuscripts and oral presentations can help clarify thinking and can be an effective way to learn technical material.

Homework assignments and examinations will often ask you to explain something or to define something that you have been taught. In addition, each of the projects is communications intensive. For each project, you and your partner must submit a written proposal and revise the proposal until it is approved by the staff. For each project, you and your partner must prepare a formal report that is structured as a scientific paper or an oral presentation. First drafts of each report are due approximately one week before the final drafts, and will be reviewed by the technical staff, staff from the MIT Writing Program, and by student peers. You and your partner will be assigned to prepare a written critique of a first draft from a different team. The critiques will be discussed during a special recitation session held between the first draft and final draft deadlines.

EECS students can satisfy their junior year communications requirement in their major (CI-M) by taking this subject. Phase 2 credit can also be awarded by the Writing Program to students who receive a B or higher grade for their participation in the writing clinic and for communication skills demonstrated in this subject.

Student-Staff Responsibilities

You, the student, have a right to expect the staff to be prepared and responsive and punctual. While we cannot always deliver entertaining and incisive lectures and recitations, you have a right to expect us to act professionally. The staff will be available for consultation at mutually agreeable times. We expect to return all graded problem sets and exams within one week of submission and all experimental project reports within three weeks of submission. The theoretical project report will be returned at the end of the semester.

We also have expectations for you. We expect you to do the work and to submit your work on time! Furthermore, we expect that the work you submit to us under your name is your work. Interaction of students on the concepts involved in the homework assignments is often helpful and is encouraged, but each student should work out his/her own solutions. Submitted homework should reflect the knowledge of the individual. If you do work with other students, please include their names on your problem sets. Submission of problem sets that are copies of solutions previously distributed in this subject is immature, dishonest, a waste of everyone's time, and a discredit to the perpetrator. In general, submission of work that is not your own - in the form of solutions to homework assignments, laboratory reports, proposals, or reports - constitutes plagiarism and is as serious an offense as is cheating on examinations.

Grade

Because of the variety of work in this subject, grades do not depend heavily on performance on any single assignment or examination. The letter grade for the subject will be determined from a weighted sum of letter grades for the homework assignments, projects, and examinations.

The weighting factors are:

| Activities | Percentages |

|---|---|

| Homework | 5% |

| Exam I | 15% |

| Exam II | 20% |

| Lab Project | 15% |

| HH Project | 15% |

| Final Exam | 30% |

For students near grade boundaries, other factors may be taken into account, including participation in class, laboratory performance not evidenced in the laboratory grade, etc. The grades are determined by the staff. Students registered for undergraduate and graduate versions of this subject will be graded separately.

Texts

The course text has two volumes:

Weiss, Thomas F. Cellular Biophysics: Transport. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996. ISBN: 9780262231831.

Weiss, Thomas F. Cellular Biophysics: Transport. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996. ISBN: 9780262231831.

———. Cellular Biophysics: Electrical Properties. Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996. ISBN: 9780262231848.

———. Cellular Biophysics: Electrical Properties. Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996. ISBN: 9780262231848.

For the portion of the subject that deals with electrical properties of cells, supplementary reading is available in the following texts:

Vander, Arthur J., James H. Sherman, and Dorothy S. Luciano. Human Physiology, The Mechanisms Body Function. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1998. ISBN: 9780070670655.

Vander, Arthur J., James H. Sherman, and Dorothy S. Luciano. Human Physiology, The Mechanisms Body Function. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1998. ISBN: 9780070670655.

Aidley, David J. The Physiology of Excitable Cells. 4th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN: 9780521574211.

Aidley, David J. The Physiology of Excitable Cells. 4th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN: 9780521574211.

Kandel, Eric R., James H. Schwartz, and Thomas M. Jessell. Principles of Neural Science. New York, NY: Elsevier, 1991. ISBN: 9780444015624.

Kandel, Eric R., James H. Schwartz, and Thomas M. Jessell. Principles of Neural Science. New York, NY: Elsevier, 1991. ISBN: 9780444015624.