Convolution as a superposition of impulse responses. Modeled on the MIT mathlet Convolution Accumulation.

In this unit we will learn two new ways to represent certain types of functions, and these will help us solve linear time invariant (LTI) DE's with these functions as inputs.

We start with Fourier series, which are a way to write periodic functions as sums of sinusoids. In Unit Two we learned how to solve a constant coefficient linear ODE with sinusoidal input. Now using Fourier series and the superposition principle we will be able to solve these equations with any periodic input.

Next we will study the Laplace transform. This operation transforms a given function to a new function in a different independent variable. For example, the Laplace transform of ƒ(t) = cos(3t) is F(s) = s / (s2 + 9). If we think of ƒ(t) as an input signal, then the key fact is that its Laplace transform F(s) represents the same signal viewed in a different way. The Laplace transform converts a DE for the function x(t) into an algebraic equation for its Laplace transform X(s). Then, once we solve for X(s) we can recover x(t).

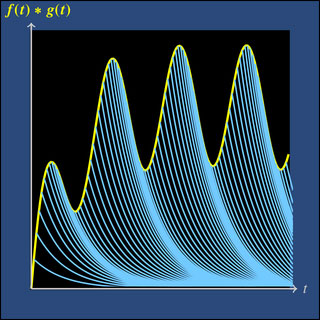

In the course of this unit, two important ideas will be introduced. The first is the convolution product of two functions. At first meeting this operation may seem a bit strange. Nonetheless, as we will see, it arises naturally, and the Laplace transform will allow us to work easily with it.

The second important idea is the delta function. Up to now all inputs to our systems have caused small changes in a small amount of time. An impulse is an input that causes a sudden jump in the system. For example, a sharp blow to a mass will cause its momentum to jump. The delta function is a mathematical idealization of an impulse and one which allows us to handle DE's with these types of inputs.