Link to Paul (PJ) Folino's Page on Tumblr

Contents

- Day 1 Pitch

- Day 2 Script

- Day 3 Trailer: Subdivision Pitch

- Day 4 Storyboard

- Day 5 Script

- Day 6 Script

- Day 7 Script

- Day 8 Shot List

- Day 11 Rough Cut

- Day 13 Final Project

- Science Out Loud

Day 1 Pitch: The Science of Poaching an Egg Pitch

> Download from iTunes U (MP4 - 6MB)

> Download from Internet Archive (MP4 - 6MB)

This video is courtesy of Paul Folino on YouTube and is provided under our Creative Commons license.

I have never been able to poach an egg well. Come to find out, there is a lot of science behind poaching eggs!

Food for thought: Did you know there are statistical correlations between how you cook your eggs and how happy you are?

Day 2 Script

Title: Thinking about Sinking

I. Introduction

Setting: Nautical Museum in Building 5

- Paul (walking): As long as people have lived on this planet, there have been boats. Many of the model boats shown in this museum are over 100 years old, but evidence suggests that the oldest ones date back to log boats, almost 10,000 years ago.

- But now, when we look out onto the harbor, it is clear that we have advanced since the times of hollowed out trees. Today, there are all types of ships such as… (pause) (Video on specific ship / audio) containerships, oil tankers, and cruise ships, among many others.

- (Back to Boston Harbor) But as we got better in the design of ships, so did we venture away from the safe haven of the shore and into rough and dangerous seas (transition to next picture).

- (Break to video clip or picture in motion of the Titanic sinking, just audio) Now we are all familiar with vessels like the Titanic, which sank on her maiden voyage and lost 1,517 lives in the frigid waters of the North Atlantic. But what if I were to tell you that a basic design flaw is what caused the Titanic to sink?

- In this video, I will show you how the advanced vessels of today are able to stay afloat, even after suffering extensive damage. I am going to introduce to you the idea of "subdivision."

Camera view pans on vessel traffic in Boston Harbor then focuses and zooms on Paul.

II. Body

Setting: Tow Tank

- As a Coast Guard Marine Inspector and naval architect, that is a "ship designer," I sometimes lose sleep over the thought of a vessel sinking. The idea that a mariner or boat enthusiast would not be able to return to his or her family is troubling, but luckily engineering can help resolve it!

- This is because many ships are subdivided into watertight compartments by walls, called bulkheads, and floors, called decks. When a ship is damaged, only certain compartments are flooded instead of the whole ship.

- To demonstrate this concept I have three box barge models. One is the ORCA, and it has no subdivision, that is, no bulkheads or decks, as you can see. The other is the ISHMAEL and it has subdivision. The last vessel is the TITANIC II, and it has subdivision but it does not connect to the uppermost deck.

- Now to demonstrate that each of these models are watertight to begin with, I will place them all in the water and wait 5 minutes to ensure they float and do not sink. (Fast forward the 5 minutes of waiting time).

- Great, they all float in the undamaged condition. Now I will take the ORCA and cut a 1-inch hole into its side. (Show cutting hole and place in water)… As we can see water is rushing into the vessel and since there is no structure to stop this, the vessel fills with water and sinks.

- As you may already know, objects float and sink for a variety of reasons. Materials like wood, foam, and ice float because they are less dense than water. But shipbuilding materials like steel and aluminum are denser than water. So how does this happen?

- Archimedes, of course!

- Archimedes was a Greek mathematician long ago. The story goes that he was in the bathtub when he discovered that the weight of an object is equal to the mass of water it displaces. He was so excited about his discovery that he ran through the streets naked screaming "Eureka!"

(Have easel with white paper to describe this concept)

- This can simply be explained by the following: if the weight of an object divided by its volume is greater than 1, it will sink, if less than 1 it will float. If it equals one it remains neutrally buoyant, like a submarine.

- (Perform calculation on paper) So if we take the weight of the box barge and add the weight of water currently inside of it and divide it by its volume we find it will be greater than 1, therefore it sinks.

- Now we take the subdivided barge and damage it in the same area (pick up second barge and cut hole in it, place in water)… as you can see water stops flowing into the barge because the bulkhead blocks it from progressing. This results in the barge angled or trimmed in the water but it has not yet sunk.

- (Perform calculation on easel) Again if we take the weight of the water added to the 1 compartment and add the weight of the barge and then divide it by its volume, our density is still less than 1 so it floats, just in a trimmed condition. Trim occurs because the distribution of weight on the vessel is uneven, like being on a see-saw with one person.

- (Now pick up other barge) Now we look at the Titanic II. The RMS Titanic was described as the "unsinkable" ship but we all know that is not true. Can you imagine what will happen to the ship if we damage this compartment with an iceberg? (Damage and place in tank).

- (As model is sinking) The lead designer of the Titanic, Thomas Andrews, did not require the bulkheads to connect with the watertight deck above. This resulted in progressive flooding into adjacent compartments and just like the ORCA, resulted in the vessel sinking.

(Cut to moving image of Archimedes in bathtub, just audio)

III. Conclusion

1. In conclusion, subdivision is used on vessels for many reasons, one of which is to ensure the ship doesn't sink! As a naval architect, you will be ensuring that people on ships are safe by knowing how to divide the compartments. The job carries a lot of responsibility, as does any engineering discipline, but by using science and math we can make sure that your loved ones return safely from the sea!

Day 3 Trailer: Subdivision Pitch

> Download from iTunes U (MP4 - 8MB)

> Download from Internet Archive (MP4 - 8MB)

This video is courtesy of Paul Folino on YouTube and is provided under our Creative Commons license.

The actual prototype is being thought of / designed. This subdivided "barge" WILL sink.

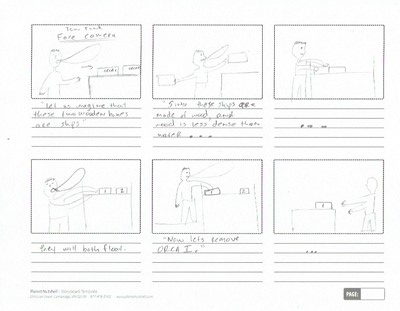

Day 4 Storyboard

I am still refining the script.

Day 5 Script

Title: Thinking about Sinking

(@ Tow Tank / Vorticity Tank, civilian clothes) Paul: Let us imagine that these two boxes here, ORCA I and ORCA II, are ships. They kind of look like barges.

Since foam is less dense than water, we know that they'll both float (place 2 boxes on top of the water).

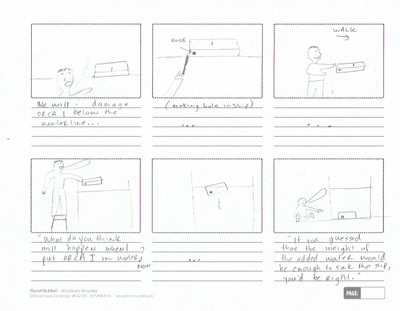

Now, lets take ORCA I out of the water and damage it below the waterline (Take ORCA I out of water and cut hole into box).

What do you think will happen when I put ORCA I in the water? (motion of putting box in water)(Go to GoPro footage while box is sinking)

If you guessed that the weight of the added water would be enough to sink her (while sinking, still GoPro)… (cut to CU of box at bottom of tank with Paul) you'd be right (box sinks)

Now let's take ORCA II and damage it in the same spot and see what happens (Grab vessel, walk over to table, create same damage, place in water, doesn't sink).

You can see that ORCA II did not sink, although it is trimmed, that means angled, to the bow. So, why did ORCA II, a seemingly identical ship, not sink? How do we prevent ships from sinking? (pause)

The answer lies in subdivision.

(B-Roll of sound and showing fast forward vessel traffic at a container terminal / cruise ships, harbor traffic, etc?)

(At Hart Nautical Collection @ MIT Museum with Hereshoff half hulls as a backdrop) If we remove the tops of both ships, called the weather deck, and take a look inside (Video a close up of removing the decks, just audio voice), (back to presenting) we can see that ORCA II is divided into compartments by these walls called transverse bulkheads, while ORCA I is not.

These compartments are watertight which means that they can be filled with water, without leaking into other compartments (look at camera). This subdivision reduces the amount of water that can enter the vessel if damaged. So a ship can be damaged and still not sink!

(Top down angle, showing the ships) So why don't we just add hundreds of watertight bulkheads, then the ship would never sink? Now remember, most ships are made with materials that sink, like steel, so lets have Archimedes help answer this!

(Back at Tow Tank) Archimedes was a Greek mathematician long ago. The story goes that he was in the bathtub when he discovered that the weight of an object is equal to the weight of water it displaces.

(Different camera angle) In other words, if we take the underwater volume of the ship and fill it with water, we get the weight of the ship. (Animation, highlight the underwater volume of ship) This is best described by Archimedes Principle which states that the Force of Buoyancy = the weight of a unit volume of water times the underwater volume of the ship.

(@ Tow Tank, CU, boxes out of focus in backdrop) So what does this have to do with subdivision? Well, if we pretend the box is steel, and we kept adding more watertight bulkheads, which I have indicated by these weights, then the ship would get heavier, causing a larger underwater volume.

You may be asking, "So what! As we have learned, the force of buoyancy equals the weight of the water displaced, so with more underwater volume, there is more upward buoyant force."

You would be correct. But it gets to a point where if we add too much weight, the ship cannot produce any more upward buoyant force.

(Animation on top of still picture of boxes) A basic way to describe it is like this. If we take a steel vessel and fill it with more and more steel bulkheads, so much so, that it resembles a solid piece of steel, than it will sink as we already know. In effect, we have taken out all of the air in the vessel, and replaced it with a dense metal. So the density turns out to be greater than 1 and the ship sinks!

(Pratt School Museum, in uniform) As a Coast Guard Marine Inspector and naval architect, I have lost sleep over the thought of ships sinking and people being injured. We have to ensure that people on ships are safe by knowing how to divide the compartments. The job carries a lot of responsibility, as does any engineering discipline, but by using science and math we can make sure that our loved ones return safely from the sea!

Day 6 Script

When we take really complex things and break them down into smaller pieces, we find out that we know a lot more about things than we think.

(@ Tow Tank / Vorticity Tank) Let's take this foam box, ORCA I, and cut a hole in it (cut hole in box). Now let's put this box in the water and see what happens (box sinks). The box sinks due to the weight of the added water. But what if it contained cargo, or oil, or even people?

Now let's take ORCA II and do the same thing.

(Go Pro footage of cutting hole from inside and sinking / just audio)

(facing camera) You can see that ORCA II didn't sink, although it's sitting at an angle. So, why didn't ORCA II sink?

(New angle) As easy as it sounds, this simple demonstration is essential to the design of huge, complex ships; ships that are responsible for safely transporting 90% of all our stuff.

As naval architects, how do we design ships carrying our stuff to make it into port safely, and not sink? Well, why don't we find out…

(At Hart Nautical Collection @ MIT Museum with Herreshoff half hulls as a backdrop)

Here we have ORCA I and ORCA II from before. Even though these boxes don't engage in international trade, they behave just like a thousand foot cargo ship would.

If we remove the tops of both boxes and take a look inside (Video a close up of removing the decks, just audio voice), (back to presenting) we see that ORCA II is divided into compartments by these walls called transverse bulkheads, while ORCA I isn't. These compartments are watertight (point to ORCA II compartments); even if damage occurs in this part of the ship, water rushing in won't go into other compartments because the damage is isolated. We refer to ORCA II as being subdivided.

(Back to CU) It's unclear when subdivision started being used in boat building, but accounts of Chinese trade ships as far back as the 5th century, show that water could enter ships without sinking. So let's find out why this happens.

Well, when we divide the ship into watertight compartments, we are limiting the amount of water that can enter it. If we divided a ship into 10 equal size compartments, and one sprung a leak, then only that compartment would flood. This would cause the ship to heel and trim, but it wouldn't cause a complete loss of ship and cargo, and the ship would hobble into port and get repairs. But why does this all matter?

Because ships are huge! And they carry tons of stuff we need. Ships can be up to a quarter mile long and can carry millions of dollars worth of cargo. So by subdividing ships we are ensuring the safe delivery of all our stuff.

Ships still sink though. It's expensive and impractical to design the "unsinkable ship," especially when a ship would never see that amount of damage. For that reason, naval architects consider the likelihood of damage when designing a ship.

(In Naval Construction design lab, simulation on desktop behind me) Computers make it easy to simulate certain damaged cases in practically no time. With different software we can damage certain compartments and see how the ship responds to it. This gives the designer a good idea of what parts to improve on the ship, if any.

So even though ships might seem like these complicated, intricate things… they are really just based on physical principles that we already know.

Day 7 Script

When we take really complex things and break them down into smaller pieces, we find out that we know a lot more about things than we think.

(@ Tow Tank / Vorticity Tank) Let's take this foam box, ORCA I, and cut a hole in it (cut hole in box). Now let's put this box in the water and see what happens (box sinks). The box sinks due to the weight of the added water. But what if it contained cargo, or oil, or even people?

Now let's take ORCA II and do the same thing.

(Go Pro footage of cutting hole from inside and sinking / just audio)

(facing camera) You can see that ORCA II didn't sink, although it's sitting at an angle. So, why didn't ORCA II sink?

(New angle) As easy as it sounds, this simple demonstration is essential to the design of huge, complex ships; ships that are responsible for safely transporting 90% of all our stuff.

As naval architects, how do we design ships carrying our stuff to make it into port safely, and not sink? Well, why don't we find out…

(At Hart Nautical Collection @ MIT Museum with Herreshoff half hulls as a backdrop)

Here we have ORCA I and ORCA II from before. Even though these boxes don't engage in international trade, they behave just like a thousand foot cargo ship would.

If we remove the tops of both boxes and take a look inside (Video a close up of removing the decks, just audio voice), (back to presenting) we see that ORCA II is divided into compartments by these walls called transverse bulkheads, while ORCA I isn't. These compartments are watertight (point to ORCA II compartments); even if damage occurs in this part of the ship, water rushing in won't go into other compartments because the damage is isolated. We refer to ORCA II as being subdivided.

(Back to CU) It's unclear when subdivision started being used in boat building, but accounts of Chinese trade ships as far back as the 5th century, show that water could enter ships without sinking. So let's find out why this happens.

Well, when we divide the ship into watertight compartments, we are limiting the amount of water that can enter it. If we divided a ship into 10 equal size compartments, and one sprung a leak, then only that compartment would flood. This would cause the ship to heel and trim, but it wouldn't cause a complete loss of ship and cargo, and the ship would hobble into port and get repairs. But why does this all matter?

Because ships are huge! And they carry tons of stuff we need. Ships can be up to a quarter mile long and can carry millions of dollars worth of cargo. So by subdividing ships we are ensuring the safe delivery of all our stuff.

Ships still sink though. It's expensive and impractical to design the "unsinkable ship," especially when a ship would never see that amount of damage. For that reason, naval architects consider the likelihood of damage when designing a ship.

(In Naval Construction design lab, simulation on desktop behind me) Computers make it easy to simulate certain damaged cases in practically no time. With different software we can damage certain compartments and see how the ship responds to it. This gives the designer a good idea of what parts to improve on the ship, if any.

So even though ships might seem like these complicated, intricate things… they are really just based on physical principles that we already know.

(nothing really changed from before)

Day 8 Shot List

Sinking Scene shots

Locations:

Hart Nautical Collection, MIT Museum (01 / 14 / 15 1300-1500)

Marine Robotics Lab (01 / 15 / 15 1400-1500)

Pratt Ship Museum (01 / 15 / 15 TBD)

Naval Engineering Lab (01 / 16 / 15 TBD)

Scene 1

(Marine Robotics Lab)

(Outside doorway of lab)

"When we take really complex things and break them down into smaller pieces, we find out that we know a lot more about things than we think."

[Fast forward to entering the door and holding box]

(In lab, CU showing box and Paul) Let's take this foam box, ORCA I, and cut a hole in it (cut hole in box, show to camera). (High angle to show box in water) Now let's put this box in the water and see what happens (cut to GoPro footage, box sinks). (Retrieving box from bottom of tank) The box sinks due to the weight of the added water. (Pulling from water, CU, off to side to allow for picturres) But what if it contained cargo, or oil, or even people?

Now let's take ORCA II and do the same thing.

(Go Pro footage of cutting hole from inside and sinking / just audio)

(facing camera) You can see that ORCA II didn't sink, although it's sitting at an angle. So, why didn't ORCA II sink?

(Sitting down holding both boxes,?) As easy as it sounds, this simple demonstration is essential to the design of huge, complex ships; ships that are responsible for safely transporting 90% of all our stuff.

(New angle) As naval architects, how do we design ships carrying our stuff to make it into port safely, and not sink? Well, why don't we find out…

To Shoot:

Outside Marine Robotics Lab

- CU of PJ explaining "complex things" (keep rolling).

- CU of PJ standing with box in hand, cutting hole in box then CUT to high angle shot of placing boat in water.

- GoPro footage of box sinking.

- CU of PJ standing in same spot as part 2, but with ORCA II, cutting hole in box.

- GoPro Footage of ORCA II not sinking.

- CU of PJ offset in frame with ORCA II angled in background.

Scene 2

(At Hart Nautical Collection @ MIT Museum with Herreshoff half hulls as a backdrop)

(CU showing two boxes) Here we have ORCA I and ORCA II from before. Even though these boxes don't engage in international trade, they behave just like a thousand foot cargo ship would.

If we remove the tops of both boxes and take a look inside (Video a close up of removing the decks, just audio voice), (point to ORCA II's bulkheads, point to ORCA I's lack of bulkheads) we see that ORCA II is divided into compartments by these walls called transverse bulkheads, while ORCA I isn't.

(New angle, same setting as above) These compartments are watertight (point to ORCA II compartments); (camera roll from boat up to CU) even if damage occurs in this part of the ship, water rushing in won't go into other compartments because the damage is isolated.

(In plans room with ships plans laid out) We refer to ORCA II as being subdivided, and we can see subdivision in many of these ship's plans (CU to pointing to subdivision).

(Back to CU) It's unclear when subdivision started being used in boat building, but accounts of Chinese trade ships as far back as the 5th century, show that water could enter ships without sinking. So let's find out why this happens.

To Shoot:

- CU of PJ's with two boxes, CUT to…

- CU of PJ's hands pointing to ORCA II's bulkheads and lack of ORCA I bulkheads (just audio)

- CU of PJ hands pointing to ORCA I and II, roll camera up to PJ

- PJ off to side leaning over plan's but turned camera to see subdivision in ship's plans, ducks and splines around plans (Possible "… many ships plans" could be images in video of vessel plans with subdivision)

- Plans in background, PJ on stool CU.

Scene 3

(Animation, possible live reshoot) When we divide the ship into watertight compartments, we are limiting the amount of water that can enter it. If we divided a ship into 10 equal size compartments, and one sprung a leak, then only that compartment would flood. This would cause the ship to heel and trim, but it wouldn't cause a complete loss of ship and cargo, and the ship would hobble into port and get repairs. But why does this all matter?

(Plans in front of me, MIT museum) Because ships are huge! And they carry tons of stuff we need. Ships can be up to a quarter mile long and can carry millions of dollars worth of cargo. So by subdividing ships we are ensuring the safe delivery of all our stuff.

To Shoot:

- See Scene 2, Part 4.

Scene 4

(In Naval Construction design lab, simulation on desktop behind me) Ships still sink though. It's expensive and impractical to design the "unsinkable ship," especially when a ship would never see that amount of damage. So that's why we use computers to help us out with subdivision.

(Screen record of POSSE) Computers make it easy to simulate certain damaged cases in practically no time. With different software we can damage certain compartments and see how the ship responds to it.

This gives the designer a good idea of what parts to improve on the ship, if any.

So even though ships might seem like these complicated, intricate things… they are really just based on principles that we already know.

To Shoot:

- CU of PJ (PJ Turns to camera)

- Video recording of POSSE simulation

- See Part 1

Rough Cut

> Download from iTunes U (MP4 - 13MB)

> Download from Internet Archive (MP4 - 13MB)

This video is courtesy of Paul Folino on YouTube and is provided under our Creative Commons license.

Final Project

> Download from iTunes U (MP4 - 11MB)

> Download from Internet Archive (MP4 - 11MB)

This video is courtesy of Paul Folino on YouTube and is provided under our Creative Commons license.

Creative Commons: CC BY-NC-SA, MIT

Hosted By: Paul Folino

Written By: Paul Folino

Additional scripting: Elizabeth Choe, Jaime Goldstein, Ceri Riley, George Zaidan, students of 20.219

See the full credits on the course Tumblr.

Science Out Loud

Paul's video was professionally produced by Science Out Loud after this course finished.

> Download from iTunes U (MP4 - 9MB)

> Download from Internet Archive (MP4 - 9MB)

This video is from MITK12Videos on YouTube and is provided under their Creative Commons license.