TimeMap

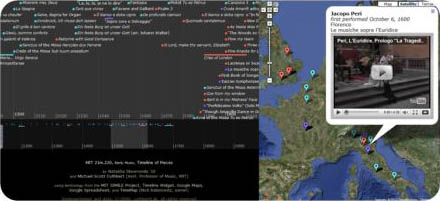

TimeMap helps you to explore and compare music that was composed at the same time and/or in close geographical proximity. (TimeMap is best viewed with Firefox and Safari browsers. Image courtesy of Natasha Skowronski. Used with permission.)

One of the hardest parts of learning music history (and I suppose art and other histories as well) is that though styles change over time, the changes happen extremely scattered with little uniformity. Thus students tend to believe that a more "advanced" sounding piece was composed later than a "simpler" sounding one, when the opposite is also extremely likely to be true. One of the biggest recurring problems for learning style in Early Music, for instance, is that the most commonly studied pieces in English Renaissance style are being composed at the same time or after the Italians created new techniques of recitative, basso continuo, and other markers of the Baroque.

TimeMap, a tool developed by myself and Natasha Skowronski (MIT '10), allows viewers to see what pieces were being composed at the same time or in close geographical spans of each other. Each piece (taken from a mix of my syllabus and Craig Wright's Music in Western Civilization) has a thirty second excerpt online while a few others have associated YouTube videos.

Pythagorian Tunings

From Ancient Greece to Kendall T: The Musical Legacy of Pythagoras

This video is from MIT Council for the Arts on MIT TechTV and is not provided under our Creative Commons license.

Near MIT, inside the Kendall Square subway stop, is a musical art object by Paul Matisse called 'Pythagoras' which demonstrates the fundamental ratios of so-called Pythagorean tuning via several large bells that are struck by hammers under the control of riders waiting for their trains. In this lecture, given on the occasion of the renovation of the bells, Prof. Cuthbert discusses the musical legacy of Pythagoras 2500 years after his death. The video talks about these bells, the musical/scientific achievements of the followers of Pythagoras, modern tools for replicating their experiments, how common practice music adopted then rejected so-called Pythagorean tuning, and the modern revival of 'pure' just intonation tuning.

Monochord Simulator

This double-monochord simulation software was programmed by Michael Cuthbert to let students hear the primary ratios of Ancient Greek and early Medieval music. Most of the notes used by the Greeks are not playable on modern pianos (falling between keys), and some notes have two only slightly different forms that students can train themselves to hear. An example of this would be the difference between a ditone (ratio 81:64) and a major third (5:4 or 80:64).

The software runs on Mac OS (including Lion) and PCs (Windows 2000-Windows 7). It was made using Max/MSP.

- PC (ZIP - 2.0MB) (This ZIP file contains: 1 folder.)

- Mac (ZIP - 6.4MB) (This ZIP file contains: 2 .app files and 1 .app folder.)

NOTE: MIT OpenCourseWare does not provide support for this software.

For more about Monochords and a demonstration of this software, see the video embedded above, specifically 8:00 to 9:30.

Manuscript Research

enChanting Musical Artifacts in Unlikely Places: Rare Resources in MIT's Lewis Music Library

Prof. Michael Scott Cuthbert and Nancy Carlson Schrock, Conservator for Special Collections, MIT Libraries. March 3, 2009. (53:15) (This video is from MIT Libraries on MIT TechTV and is not provided under our Creative Commons license.)

About this video [from MIT World]: "There are times when it's necessary to judge a book by its cover, or a single page, because that's all that remains. Michael Scott Cuthbert and Nancy Schrock reveal some treasures from MIT's early music collection which, while often incomplete or damaged, sing volumes about their origins and use.

Cuthbert demonstrates that when it comes to medieval and renaissance music manuscripts, there's really no substitute for the real thing. His discussion concerns several recent additions to MIT's Lewis Music Library. Online perusal alone cannot reveal which of his manuscripts was designed to be read by a large group of singers in a cathedral, and which served as a valued part of a priest's collection for personal study. Holding the two artifacts up, Cuthbert makes it clear: He first displays a giant, two-sided leaf, and then an aged volume containing the much smaller page.

To examine these specimens, says Shrock, she must use special tools of the trade: a fiber optic light sheet for studying paper; microscopes, digital cameras. In examining and preserving music manuscripts and other rare MIT books, Schrock needs to know the process by which the object came into being. She shows the large leaf from the choir book: it's parchment, made from the lined skins of young animals, with the hair scraped off, shaved and rubbed with pumice to achieve a smooth surface perfect for text and binding. Schrock shows a 15th century book of hours, an illuminated manuscript that was rebound by a collector in the 18th century. While she admires the redo (red morocco tooled in gold), the object "no longer reflects the way this manuscript was originally made, and we've lost knowledge about it." Flaws are more informative than beauty.

Says Cuthbert, "For many of us, modern musicology is less about spending time in dusty archives and more about recreating what we see in CSI." New technology may hold the key to answering longstanding mysteries, such as the abrupt abandonment or evolution of certain kinds of religious music. Some manuscripts may hide their beginnings, or travel widely: "Maybe the choir book left the cathedral in a sack in the middle of the night" he says. With computer software, researchers can now compare music manuscripts that originated in widely separated regions of the world. New machines can peer into manuscripts where the music has been scraped off to make room for other information (such as land ownership records, or an illustrated bestiary), to see what originally existed; and advances in digital imaging can discern the flow of notes on a page where they had once been obliterated or obscured. DNA tracing, he hopes, will ultimately permit musicologists to determine the provenance of animals used in parchment down to the cathedral green where they grazed."

The Glaser Codex: A Manuscript of Liturgical Chant at MIT

The Glaser Codex comprises the remains of an approximately 107 folio (214 page) manuscript from the 15th and 16th century. This website contains a selection of folio images, along with 21M.220 student scholarly analysis of these folios.