Background

Much of what we know about the world is known with various degrees of certainty. Although many different numerical models have been proposed for representing this uncertainty, many researchers today believe that probability theory—the most extensively studied uncertainty calculus—is an appropriate basis for building computerized reasoning systems.

Mathematical Preliminaries

We take the world of interest to consist of a set of random variables, X = {X1, X2, ... , Xn}. Each of the Xi can take on one of a discrete set of values, {xi1, xi2, ... , xiki}. (Formulations using continuous variables are also possible, but we will not pursue them here. A continuous variable can, of course, be approximated by a large number of discrete values.)Each possible combination of assignments of values to each of the variables represents a possible state of this world. There are![]() such states. This is clearly exponential in the number of variables; for example, if each variable is binary, all of the ki = 2 and the number of states is 2n. Each state may be identified with the particular values that it assigns to each variable. We might have, for example, S12 = {X1 = a, X2 = e, ... , Xn = b}.

such states. This is clearly exponential in the number of variables; for example, if each variable is binary, all of the ki = 2 and the number of states is 2n. Each state may be identified with the particular values that it assigns to each variable. We might have, for example, S12 = {X1 = a, X2 = e, ... , Xn = b}.

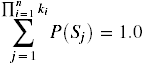

A probability function, P', assigns a probability to each of these possible states. The probability for each state, P(Si),is the joint probability of that particular assignment of values to the variables. All states are distinct, and they exhaustively enumerate the possibilities; therefore,  .

.

We will often be interested in the probability not of individual states, but of certain combinations of particular variables taking on particular values. For instance, we may be interested in the probability that {X3 = a, X5 = b}. In such cases, we wish to treat other variables as "don't cares." We call such a partial description of the world a circumstance C, and the variables that have values assigned the instantiation-set of the circumstance, I(C). ("Circumstance" is not a commonly-used term for partial descriptions of the world. People use terms such as "partially-specified state" and other equally unsatisfying terms.) The probability of a circumstance C can be computed by summing the probabilities of all states that assign the same values to the variables in the instantiation set I(C) as C. If we re-order

variables X so that the first m are the instantiation set of C, then (in a shorthand notation):

![]() .

.

For example, if the world consists of four binary variables, W, X, Y and Z, then the circumstance {X = true, Z = false} is given by

.

.

The computational difficulty of calculating the probability of a circumstance comes precisely from the need to sum over a possibly vast number of states. The number of such states to sum over is exponential in the number of "don't cares" in a circumstance.

Defining P for each state of the world is a rather tedious and counter-intuitive way to describe probabilities in the world, although the ability to assign an exponentially large number of independent probabilities would allow any probability distribution to be described. It might happen that the world really is so complex that only such an exhaustive enumeration of the probability of each state is adequate, but fortunately many variables appear to be independent. For example, in medical diagnosis, the probability that you get a strep infection is essentially independent of the probability that you catch valley fever (a fungal infection of the lungs prevalent in California agricultural areas). Formally, this means that P(strep, vf) = P(strep)P(vf). When two variables both depend on the same set of variables but not directly on each other, they are conditionally independent. For example, if an infection causes both a fever and diarrhea, but there is no other correlation between these symptoms, then P(fever,diarrhea│infection) = P(fever│infection) P(diarrhea│infection).

The independencies among variables in a domain support a convenient graphical notation, called a Bayes network. In it, each variable is a node, and each probabilistic dependency is drawn as a directed arc to a dependent node from the node it depends on. This notion of probabilistic dependency does not necessarily correspond to what we think of as causal dependency, but it is often convenient to identify them. When there is no directed arc from one variable to another, then we say that the second does not depend on the first.

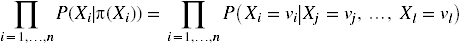

The probability of a state is a product over all variables of the probability that the variable takes on its particular value (in that state)

given that its parents take on their particular values: ![]() .

.

The right hand side is an abbreviation for  .

.

where ![]() . As described above, to find the probability of a circumstance, we must still sum over all of the states that are consistent with the circumstance — i.e., a number of states exponential in the number of "don't cares."

. As described above, to find the probability of a circumstance, we must still sum over all of the states that are consistent with the circumstance — i.e., a number of states exponential in the number of "don't cares."

Problems:

1. Your expert supplies you with the following assessment: "I think that disease D1 causes symptoms S1 and, together with disease D2, causes symptom S2. 80% of patients affected by disease D1 will manifest symptom S1, which is present in the 10% of the patients without disease D1. D1 and D2 cause the occurrence of symptom S2 in 60% of cases, when only D1 is present S2 occur in the 70% of patients, when only D2 is present S2 occur in the 80% of patients, when neither D1 or D2 occur symptom S2 occurs in the 10%. Disease D1 occurs in the 20% of the population, while disease D2 occurs in the 10%.

- Draw the network capturing the description.

- What kind of graph is this and why?

- Assume that the variables can take two values, 1 for present, 0 for absent. Write the conditional probability tables associated to each dependency in the network.

- Write down the formula to calculate the joint probability distribution induced by the network.

- Using these table, calculate; the marginal probability p(S1 = 1).

2. Neurofibromatosis-1 is an inherited disorder characterized by formation of neurofibromas (tumors involving nerve tissue) in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, cranial nerves, and spinal root nerves. Neurofibromatosis-1 is caused by a mutation in the NF1 gene.

- The Affymetrix human genome microarray probe for the gene in part c. is as follows: AAGTGCCATGTTCCTCAGATTTATC. If one starts with a sequence of length n >= 25, derive a formula for the probability that it will match a random 25 base sequence at least once assuming 1) base types are uniformly distributed within each position and 2) each base position is independent of the other.

- Using the same assumptions as above, what is the expected number of sequences that will match within the entire human genome (3x109 base pairs) going in the 5' to 3' direction (i.e. only looking in one direction).

- Using the same assumptions as above, what is the theoretical ratio of the number of serine to tryptophan amino acids in the human genome?

- Are the numbered assumptions made in question 1.a. always correct? Explain why or why not.

- Diagnosis of the disease in this question is typically done via clinical evaluation rather than by microarray analysis. Describe a use for having this gene as a probe in the HG-U133+ 2.0 Genome Array. How might it be useful in other settings in conjunction with other technologies, or in medicine in the future?

3. The following is a protein circuit perturbation-based profile. It lists which proteins are present in a particular system under different trial circumstances. In each trial (except t=0) one protein is either added or removed.

| TRIAL | PROTEIN 1 | PROTEIN 2 | PROTEIN 3 | PROTEIN 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t=0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| t=1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | removed |

| t=2 | 0 | 0 | removed | 1 |

| t=3 | 1 | removed | 1 | 1 |

| t=4 | Added | 1 | 1 | 1 |

- Find a simple expression (using only primitives AND, NOT, OR) for each protein that is consistent with this protein circuit perturbation-based profile. A protein's formula need not be consistent with the trial in which it is experimentally adjusted, but must be consistent with the other 4 trials. For another protein's formula, you may treat other proteins that were added as "1" and removed as "0."

- Your collaborators' experiments suggest that all proteins except protein 3 are involved in the p53 pathway (involved in many cancers). Based on Biocarta pathways, what are possibilities for proteins 1, 2 and 4 given the protein circuit you derived in part 1?

4. A start-up company has just implemented a new computer decision support tool for screening the general public for a type of cancer. The computer support system has a 99% chance of detecting the cancer if it exists. If there is no cancer, the computer system will incorrectly declare cancer only 0.1% of the time. The prevalence of the cancer in the general population is 0.5%.

- If the computer predicts that a patient has cancer, what is the probability that the patient, in fact, does not have cancer?

- Explain why the result is so high/low.

- It turns out that the company will let you use the product for free. What other uses can you think of for this product (other than screening as described above)?

5. In 2007, the US Food and Drug Administration approved gene expression-based test for predicting breast cancer recurrence. Technologies such as this one are often developed by looking at microarrays of gene expression (typically across all human genes) at several times points- comparing controls with disease patient samples. One way described in class involves using different dyes. Describe (in detail) an experiment using this process which could be used to find the gene expression pattern that predicts breast cancer recurrence.

6. A study finds that an innovative technique allows clinicians to find significantly smaller tumors than the previous gold standard through detecting protein interactions with tumor proteins before the tumor has a chance to grow. The study goes on to find that survival times increased in both patients with metastases and those with no metastases. Could this be true? If so how do you explain this finding? If not, why not?