(b) Taillard, et al. [1] summarize Bouvet, et al.'s [2] attempt at a yield surface for superelastic alloys; this is a modification of the von Mises equivalent stress and criterion that we have discussed. Restate this criterion and its components in terms of the symbols used in class.

von Mises

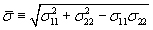

von Mises' (maximum distortion energy) criterion is "when the effective stress, defined as

![]()

exceeds the uniaxial yield stress, then the material will plastically flow." The criterion was stated by von Mises without a physical interpretation, but it is now accepted that it demonstrates the critical value of the distortion (or shear) component of the deformation energy of a body. Based on this understanding, a body flows plastically in a complex state of stress when the distortional deformation energy is equal to the distortional deformation energy in uniaxial stress (tension or compression). This criterion is also known as the J2 plasticity criterion because it is the second invariant of the stress deviator.

Mathematically, the yield function for the von Mises condition is written as

![]()

or alternatively,

![]()

where k is a critical value. Substituting the value of J2 into this equation, we obtain the von Mises yield criterion as a function of the principal stresses:

![]()

Or as a function of the stress tensor components

![]()

This equation defines the yield surface as a circular cylinder whose yield curve, or intersection with the deviatoric plane, is a circle with radius ![]() . This implies that the yield condition is independent of hydrostatic stresses, as is implied by the fact that it was derived from the deviatoric stress tensor.

. This implies that the yield condition is independent of hydrostatic stresses, as is implied by the fact that it was derived from the deviatoric stress tensor.

In the case of uniaxial stress or simple tension, ![]() , so the von Mises criterion becomes

, so the von Mises criterion becomes ![]() . Using this equation, which gives the relation between the uniaxial yield stress,

. Using this equation, which gives the relation between the uniaxial yield stress,![]() , and the pure shear yield stress, k, the von Mises criterion can also be expressed as a function of

, and the pure shear yield stress, k, the von Mises criterion can also be expressed as a function of  :

:

![]()

For this equation, the radius of the yield curve is ![]() . The yield stress

. The yield stress  is also called equivalent stress or von Mises stress,

is also called equivalent stress or von Mises stress, ![]() , which is used to predict yielding of materials under triaxial loading from results of simple uniaxial tensile tests. Thus,

, which is used to predict yielding of materials under triaxial loading from results of simple uniaxial tensile tests. Thus,

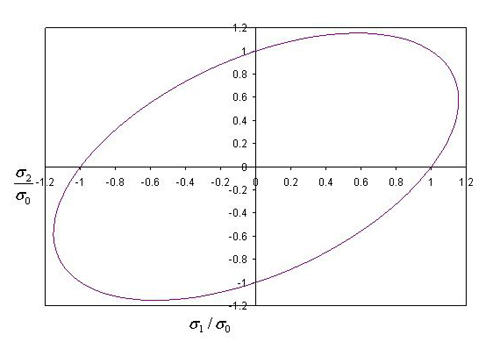

where  are the components of the stress deviator tensor. Projected into the

are the components of the stress deviator tensor. Projected into the  plane, the von Mises criterion is shown in the figure below.

plane, the von Mises criterion is shown in the figure below.

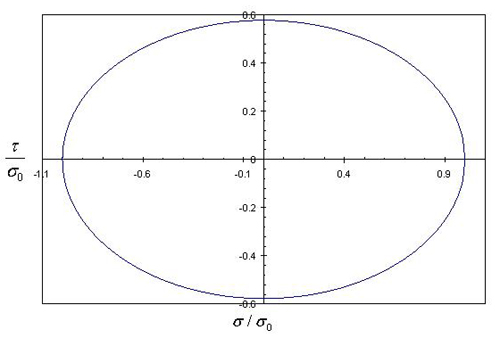

Projected into the  vs.

vs.  plane, the Von Mises criterion is shown in the figure below.

plane, the Von Mises criterion is shown in the figure below.

Taillard

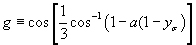

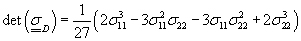

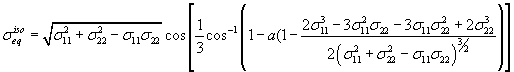

The Taillard plasticity criterion was stated as:

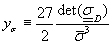

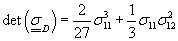

where

and a is a material constant that is determined empirically, and  is the effective stress described in the section above. In order for the above criterion to be expressed in notation consistant with the course materials, the term

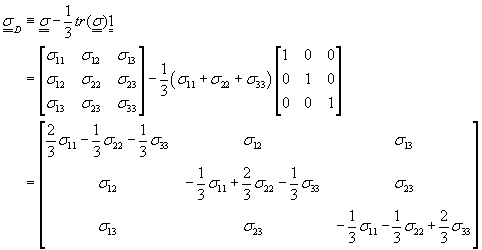

is the effective stress described in the section above. In order for the above criterion to be expressed in notation consistant with the course materials, the term  must be expanded in terms of the component scalars. First, the stress deviator is defined as:

must be expanded in terms of the component scalars. First, the stress deviator is defined as:

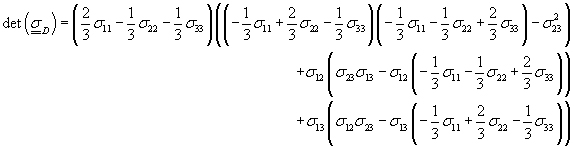

The determinant of that tensor is therefore:

Therefore, the Taillard condition can be expressed in expanded form by substituting the above expressions for  and

and  back into the original three equations that define it. I will refrain from that trivial substitution because it would be quite cumbersome for both author and reader.

back into the original three equations that define it. I will refrain from that trivial substitution because it would be quite cumbersome for both author and reader.

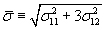

Note that the projection onto the  vs.

vs.  plane results in the simplifications:

plane results in the simplifications:

Note that the projection onto the  vs.

vs.  plane results in the simplifications:

plane results in the simplifications:

(c) Taillard, et al.'s Fig. 1 and 2 [1] demonstrate the yield surface in biaxial tension/compression and torsion for xCu-yAl-cBe, respectively. They claim Fig. 3 shows a difference between this response and that of NiTi. Graph the biaxially stressed yield surface for NiTi.

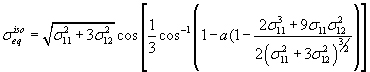

An arbitrary state of stress on the  vs.

vs.  plane can be uniquely transformed into a position on the

plane can be uniquely transformed into a position on the  vs.

vs.  plane. This can be seen on the Mohr's circle, in which any conceivable state of stress can necessarily has two points with a principal stress and zero shear stress. However, there are states of stress on the

plane. This can be seen on the Mohr's circle, in which any conceivable state of stress can necessarily has two points with a principal stress and zero shear stress. However, there are states of stress on the  vs.

vs.  plane that do not produce states of stress that fall on the

plane that do not produce states of stress that fall on the  vs.

vs.  plane. This can be seen on a Mohr's circle in which both principal stresses have the same sign, as shown below. This clearly means that data presented in the

plane. This can be seen on a Mohr's circle in which both principal stresses have the same sign, as shown below. This clearly means that data presented in the  vs.

vs.  can be transformed onto the

can be transformed onto the  vs.

vs.  plane if and only if

plane if and only if  has a different sign from

has a different sign from  .

.

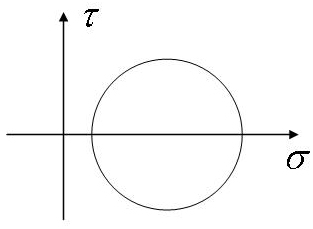

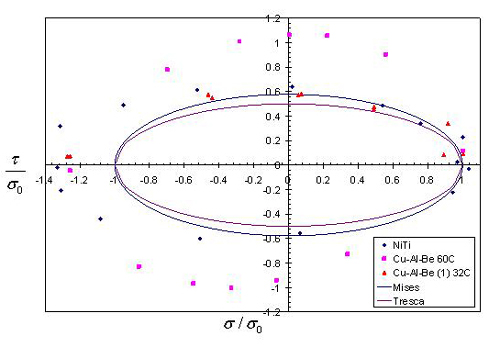

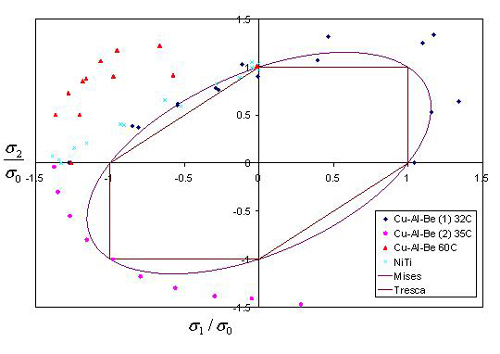

Through Mohr's circle, Taillard's figures 2 and 3 can be transformed into the  vs.

vs.  plane, and the data from the second quadrant of Taillard's figure 1 can be transformed onto the

plane, and the data from the second quadrant of Taillard's figure 1 can be transformed onto the  vs.

vs.  plane. All of this data was normalized by the uniaxial yield stress

plane. All of this data was normalized by the uniaxial yield stress  so that it produced similar magnitudes for all materials and tested temperatures. The plot below shows the all three figures normalized and plotted in the

so that it produced similar magnitudes for all materials and tested temperatures. The plot below shows the all three figures normalized and plotted in the  vs.

vs.  plane. Interestingly, The NiTi data from figure 3 agrees quite well with the Cu-Al-Be data from figure 1, but the Cu-Al-Be data from figure 2 agrees with neither.

plane. Interestingly, The NiTi data from figure 3 agrees quite well with the Cu-Al-Be data from figure 1, but the Cu-Al-Be data from figure 2 agrees with neither.

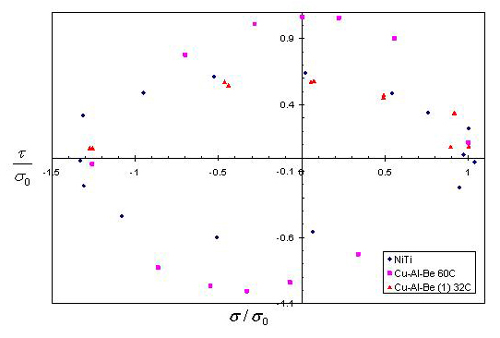

To confirm that the transformations were done correctly, the same data (except for the Cu-Al-Be primary data, for reasons stated previously) was also normalized and plotted in the  vs.

vs.  plane. Although the trend is less clear, it is still there; the NiTi data agrees better with the Cu-Al-Be data tested at 32°C than the Cu-Al-Be data tested at 60°C.

plane. Although the trend is less clear, it is still there; the NiTi data agrees better with the Cu-Al-Be data tested at 32°C than the Cu-Al-Be data tested at 60°C.

The change in yield surface between the two different temperatures for Cu-Al-Be could be explained if 60°C is above the Af temperature for Cu-Al-Be while 32°C is below the Mf temperature for Cu-Al-Be and the testing temperature for the NiTi was below that materials Mf. The changes between the two different temperatures of Cu-Al-Be would therefore represent two different phases of the material. This would indicate that the proposed yield surface would be appropriate for materials in their martensitic state but not for materials in their austenitic state. The agreement between the NiTi data and the Cu-Al-Be data taken at 32°C would indicate that the yield surface, when scaled properly, would characterize both the NiTi and Cu-Al-Be quite well.

(d) Contrast the Bouvet yield surface with the other non-asymmetric yield surfaces considered in PS3. Is this equivalent to one of them or different, and how? What is the atomistic origin of the asymmetry justifying the Bouvet yield criteria?

The yield surface presented in the papers is merely the Von Mises yield surface modified by the scalar, g:

Therefore, the yield surface is the Von Mises yield surface when g=1. This happens when a(1-yσ)=1. However, yσ is a complex function of the stress state, so there is no single parameter that causes this yield surface to degenerate to the Von Mises condition.

The yield condition presented in the papers is a curve fit of the data. Therefore, plotting the normalized source data along with the Mises and Tresca yield conditions will highlight the differences. This comparison is shown in both the  vs.

vs.  and

and  vs.

vs.  .

.

What these plots highlight is the considerable difference between the symmetrical yield conditions, which have similar behavior in the compression and tension regimes while the superlastic yield surfaces has considerably different behavior in compression (negative normal stresses).

What is the atomistic origin of the asymmetry justifying the Bouvet yield criteria? The asymmetry justifying the Bouvet yield criteria is caused by a different behavior in compression regime or in tension regime. There is a tension-compression asymmetry (or strength-differential effect) in the yield stress. Through the atomistic aspect, first of all, the different behavior in compression regime and in tension regime can be explained by atomistic bonding energy. Exceeding the Bouvet yield criteria means that the material starts yielding, that is, plastic deformation. And plastic deformation is related to bond breaking and proportional to bonding energy.

Image removed due to copyright restrictions. Please see Fig. 1 in Sleight, Arthur. "Materials Science: Zero-expansion Plan." Nature 425 (October 16, 2003): 676-676.

Compression is the regime of r < r0 and tension is the regime of r > r0. They are obviously different by intuition.

References

[1] Taillard, K. et al. "Phase Transformation Yield Surface of Anisotropic Shape Memory Alloys." Materials Science and Engineering A 438-440 (2006): 436-440.

[2] Bouvet, Cristophe, Sylvain Calloch, and Christian Lexcellent. "A Phenomenological Model for Pseudoelasticity of Shape Memory Alloys Under Multiaxial Proportional and Nonproportional Loadings." European Journal of Mechanics - A/Solids 23 (January/February 2004): 37-61.

Plasticity and fracture of microelectronic thin films/lines

Effects of multidimensional defects on III-V semiconductor mechanics

Defect nucleation in crystalline metals

Role of water in accelerated fracture of fiber optic glass

Carbon nanotube mechanics

Superelastic and superplastic alloys | Problem Set 2 | Problem Set 3 | Problem Set 5

Mechanical behavior of a virus

Effects of radiation on mechanical behavior of crystalline materials