(a) Jitsukawa, et al. [1] summarizes steel's mechanical properties by starting with tensile yield and fracture strength. Elastic behavior is not mentioned. Explain why there is no extensive database on the variation in elastic properties of steel as a function of composition, processing, or radiation exposure.

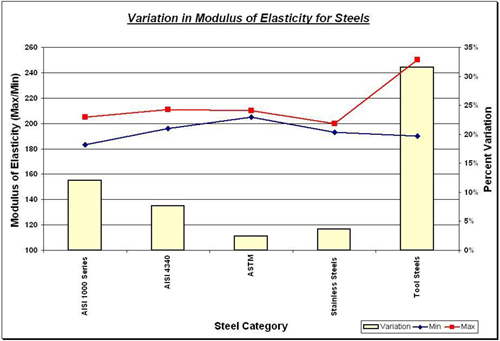

There is no extensive database on the variation in elastic properties of steel as a function of composition, processing, or radiation exposure because these values vary very little inside different classifications of steels, as can be seen in the following graph:

Data compiled from [2].

The yellow bars represent the variation of the Young's Modulus in each category, while the red and blue lines show the minima and maxima in each category. As one can see, there isn't much variation across the entire gamut of steels, with the notable exception of tool steels, though these are rarely used for large structural components such as nuclear pressure vessels due to their low ductility.

The fact that elastic properties do not vary much is because properties such as the Young's Modulus is primarily as a result of the interatomic potential, U(r) and equilibrium atomic separation, r0 :

Equation for the Young's Modulus from material covered in class.

These shall not vary much for different steels due to the fact that they are majority-iron based alloys with relatively small percentages of carbon and other alloying elements. Tool steels tend to have much larger carbon concentrations as well as significant amounts of Mo and W to obtain the desired hardness and hence have the greatest variation in Young's Modulus.

On the contrary other properties such as the yield stress and ultimate tensile strength DO vary significantly and are due to differences in composition and processing. For example 308 Stainless Steel has a yield stress of 205 MPa when fully annealed, yet this is increased by a factor 8 to a yield stress of 1660 MPa when quenched. [2]

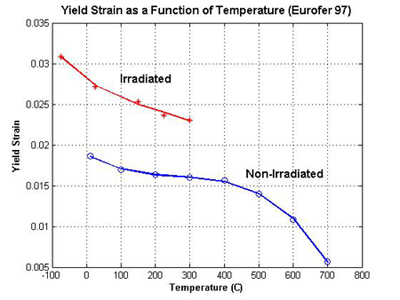

(b) Given that you know linear elastic behavior (expected of alloys like steel) is terminated at the start of plastic/permanent deformation, regraph Jitsukawa's Fig. 1 [1] in terms of yield strain as a function of operating temperature. You could consider Fig. 8 as a representative source of elastic deformation data, or glean the other papers/literature.

Fig. 2 below is a plot of yield strain as a function of temperature:

Data to create this graph taken from Fig.'s 1 and 8 of S. Jitsukawa, et al. [1]. Radiation levels for the irradiated specimen were 0.32 dpa at 300C.

In order to explain why irradiated steel would have a higher yield strain than unirradiated steel (counter-intuitive, isn't it?) one must look at the energy required for dislocations motion. In a non-irradiated crystal, one must only apply enough stress to overcome lattice friction, or at least lattice friction with a smaller number of vacancies, interstitials and voids. The entire lattice can elastically and uniformly deform only so much before dislocations get moving. In an irradiated material, there are more radiation-induced defects to pin dislocations, and therefore one must continue to apply stress until the dislocations can be unpinned. This results in more elastic deformation of the lattice required to get to the strain where dislocations will begin to move.

(c) Based on Matthews & Finnis' [3] speculation about where vacancy clusters and damage cascades occur within the crystal structure (Fig. 1), graphically represent the location and orientation of such vacancy clusters in steel. Here, you can assume a simpler alloy than the one discussed in Jitsukawa [1], Fe containing a (thermodynamic) equilibrium concentration of carbon and a supersaturation of vacancies.

First of all, assume that the steel is BCC iron with a normal amount of carbon atoms on octahedral interstitial site at a low concentration - typically around 0.5% for a medium carbon steel. Normally it is very difficult to form vacancies on the Fe lattice, but radiation can knock just about any atom off its lattice site, so we assume a supersaturation of Fe vacancies. In addition, there would likely be a large number of vacancies from the steel having been quenched, since the equilibrium number of vacancies at a given temperature is given by (Cv = n*e(-Q/RT), where Q is the activation energy and T is the temperature. Since Q does not change, and the concentration (Cv ) is frozen in place at a higher T, there are many more vacancies than usual.

We have learned from 3.21 that forming an interstitial is more difficult than forming a vacancy. However, once an interstitial is formed, it tends to diffuse much faster than a vacancy. Furthermore the high amount of radiation present in a reactor would eliminate that barrier, so a damage cascade from a fast neutron (for example) will include a number of vacancies and interstitials. The interstitials will tend to diffuse away, while the vacancies are more likely to stay put as well as become trapped by other vacancies, forming voids in regions of high vacancy concentration, as shown in Fig. 1 of Matthews & Finnis, et al. [3]

In the voids, there could be as many as two vacancies per unit cell, as a BCC unit cell contains two full atoms. In vacancy rich regions not encompassed by voids, there could be any number of vacancies per unit cell (below two), where the vacancy concentration drops with distance away from any vacancy-rich core.

References

[1] Jitsukawa, S., et al. "Recent Results of the Reduced Activation Ferritic/Martensitic Steel Development." Journal of Nuclear Materials 329-333 (2004): 39-46.

[2] MatWeb.

[3] Matthews, J. R., and M. W. Finnis. "Irradiation Creep Models - An Overview." Journal of Nuclear Materials 159 (1988): 257-285.

Plasticity and fracture of microelectronic thin films/lines

Effects of multidimensional defects on III-V semiconductor mechanics

Defect nucleation in crystalline metals

Role of water in accelerated fracture of fiber optic glass

Carbon nanotube mechanics

Superelastic and superplastic alloys

Mechanical behavior of a virus

Effects of radiation on mechanical behavior of crystalline materials | Problem Set 2 | Problem Set 3 | Problem Set 5