| |

Japan’s emergence as a modern nation can be dated very precisely. It began in 1854.

For over 200 years until that date, the country’s samurai leaders had enforced a policy of seclusion from the outside world. With but a few exceptions (Koreans, Chinese, Dutch merchants confined to a man-made island in Nagasaki), no foreigners were permitted to enter Japan. All Japanese were prohibited from leaving. Christianity was proscribed, and “Western learning” was confined largely to a tiny group of samurai in Nagasaki.

This “closed country” (sakoku) policy was abandoned only under irresistible pressure from outside, led by the United States. In 1853, four warships commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry appeared unannounced in Edo Bay, close to the capital city of Edo (present-day Tokyo) from which the warrior government ruled Japan. The government, known as the Bakufu, was headed by a hereditary supreme commander (shogun) chosen from the powerful Tokugawa clan. The entire country was divided into close to 250 domains, each headed by a daimyō or local lord.

Perry demanded that Japan open relations with America, and informed the Bakufu that he would return the following year for its response.

The commodore’s 1853 squadron included two warships of a kind never seen in Japan: fueled by coal and powered by steam-driven paddlewheels. When he returned in 1854, Perry had added a third mechanized warship and more than doubled the overall size of his fleet. On both occasions, he made clear that he would not hesitate to use force if his “pacific overtures” were rebuffed. He spoke of being able to marshal 50 warships, or even a hundred, if need be. He reminded the Japanese of the recent victorious U.S. war against Mexico—which had, indeed, added California to the United States and paved the way for swift passage of American ships across the Pacific Ocean.

|

|

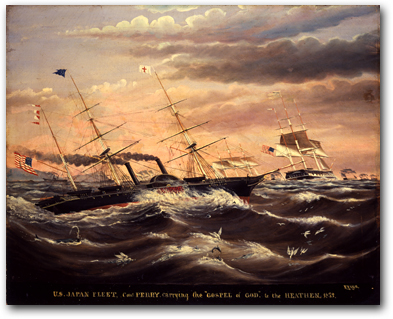

“U.S. JAPAN FLEET. Com. PERRY carrying the ‘GOSPEL of GOD’ to the HEATHEN, 1853”

James G. Evans, oil on canvas

Chicago Historical Society

[10_010]

|

The Bakufu had no real choice, and on March 31, 1854, the two sides signed the historic Treaty of Kanagawa. The “closed country” policy associated with over two centuries of isolation and security was dead and gone, replaced by an “open country” (kaikoku) policy. However reluctantly, Japan had taken the first step toward joining the quarrelsome and perilous family of nations.

The terms of the Treaty of Kanagawa were, on the surface, very modest. Japan agreed to provide hospitality for shipwrecked sailors (the Americans were most concerned with whalers at this time), and to open two ports for access to supplies. The designated ports were Hakodate and Shimoda—the latter being, as it turned out, an inconvenient location with a poor harbor. As one diplomatic historian (Tyler Dennett) later put it, “the treaty was hardly more than a shipwreck convention, the necessities of distressed mariners being amply provided for.”

Of particularly great consequence, however—although the Japanese hardly realized it at the time—the 1854 treaty also provided for the establishment of a U.S. consulate in Shimoda after 18 months had passed. It was this provision that laid the groundwork for the negotiation of full-scale commercial relations between Japan and the outside world.

The first U.S. consul general, Townsend Harris, arrived in Shimoda in August 1856 and labored painstakingly for almost two years before he succeeded in concluding a commercial treaty with the Bakufu. He spent much of his time trying to persuade the shogun’s reluctant officials that if they did not work things out with the United States, the more aggressive British would soon show up and force more onerous terms upon them—just as they were doing in China. (A Japanese transcript of Harris’s arguments has him warning that “the English Government hopes to hold the same kind of intercourse with Japan as she holds with other nations, and is ready to make war on Japan.” The American envoy, in this account, went on to talk about British desires to take possession of “Yezo”—present-day Hokkaido—as a buffer against Russia, and also warned of the evils of the opium trade that the British had forced on China.)

Townsend Harris

portrait by James Bogle, 1855

City College, New York

|

The Harris Treaty—formally titled The United States-Japan Treaty of Amity and Commerce—was signed aboard the U.S. warship Powhatan (Perry’s flagship in 1854) in Edo Bay on July 29, 1858, and began to come into effect one year later. With this, the country was “opened” to an influx of foreigners and foreign influence that went far beyond anything the Japanese had imagined when they were dealing with Perry. There was no turning back—although it took another decade for dissident samurai furious at the abandonment of the seclusion policy to realize this. Click here to read the Harris Treaty.

The Harris Treaty called for the exchange of diplomatic representatives and the opening of five ports to unimpeded trade. American citizens were granted the right to reside in designated areas, and the further right of enjoying “extraterritorial” privileges—meaning they were not subject to Japanese law, and could only be tried in consular courts under the laws of their own nation. The treaty also provided for a low fixed scale of duties on imports—meaning that Japan could not erect high tariff barriers to protect native enterprises. By 1866, duties had became fixed at 5 percent for almost all foreign items, with no clear provisions for when these exceedingly low rates would be terminated.

Additionally, the Harris Treaty incorporated a significant victory over British trade practices in the Far East by explicitly prohibiting commerce in opium. Japan was thus spared the fate of China, which had been forced to accept imports of this terribly debilitating narcotic after the notorious Opium War of 1839 to 1842.

The 1858 treaty also included a partial victory for those who defined the West’s objectives in Japan in religious terms. Christianity had entered Japan in the 16th and early-17th century, before being proscribed by the Bakufu. From the outset, many Westerners regarded the “mission” of opening Japan as a literally divine one. Trade, as one U.S. magazine put it on the eve of Perry’s departure, was but a vehicle for opening “a highway for the chariot of the Lord Jesus Christ.” While Harris failed to persuade the Bakufu to rescind its strict prohibition on the teaching or practice of Christianity among Japanese, the treaty did break the first ground in this direction by allowing the foreigners to practice their own religion in the areas open to them for residence.

The Harris Treaty also contained a provision whereby the Japanese might “purchase or construct in the United States ships of war, steamers, merchant ships, whale ships, cannon, munitions of war, arms of all kinds”—and, additionally, the Bakufu might engage “scientific, naval and military men, artisans of all kinds, and mariners to enter its service.” This provision served a double purpose. It was hoped that it would dampen Japanese fears concerning the military superiority of the foreign powers. And, of course, it opened the door to profitable military-related transactions. Under this provision, the Bakufu made its first purchase of three American paddle-wheel warships in 1862.

All this was a bonanza for the foreigner, and within a few months the Netherlands, Russia, England, and France swooped in to extract similar bilateral treaties. In Japanese lingo, these four nationalities along with the Americans became collectively known as “people of the five nations.” Prussia joined the treaty game in 1861, but the late-arriving Germans failed to make a strong enough initial impression to cause revision of the popular “five nations” rubric.

|

|

“Picture of the Landing of Foreigners of the Five Nations in Yokohama”

by Yoshikazu, 1861 (detail)

[Y0092] Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

The commercial agreements themselves were widely referred to by Japanese as the “unequal treaty system.” They denied Japan tariff autonomy. They prohibited Japanese authorities from prosecuting foreigners who committed crimes on Japanese soil. And they included a third demeaning stipulation in the form of “most-favored-nation” clauses. Under this last provision, any additional privileges another foreign nation might extract from the harried Japanese government (such as the further reductions of import duties that took place between 1858 and 1866) would also be extended to one’s own nation.

|

|

|