| |

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 captured the attention of the world—partly because it represented a new level of “modern” warfare; partly because it offered an almost mesmerizing high-stakes confrontation between “East” and “West”; and partly because new modes of communication made it possible to share graphic images of the war with popular audiences everywhere.

One of these new modes of mass communication involved photographs. Photos began to be reproduced in periodicals in the late-19th century, when advances in printing made this possible, but they really came into their own as illustrations in books and magazines around the time of the Russo-Japanese War.

The other great communications break-through was picture postcards, which coincidentally also burst onto the world scene just prior to the war between Japan and Russia. The postcard boom came about when national and international postal regulations were adopted that permitted the private manufacture and mailing of these lively popular graphics.

Although the war pitted Imperial Japan against Tsarist Russia, other powers also had a stake in the outcome. Japan financed the war in considerable part by raising loans in London and New York.

By virtue of the bilateral military alliance it entered into with England in 1902, moreover, Japan was able to take on Russia without fear that any other nation would come in on Russia’s side (for this would have triggered England joining the war in support of Japan). Russia, on its part, looked to France for financial help and counted Germany as a sympathetic bystander.

Foreign journalists and military attachés flocked to Asia to observe titanic battles on land and sea first-hand. Photographers found an international audience for their largely black-and-white (occasionally tinted) images—and so did graphic artists, whose war paintings and drawings were now commonly replicated not merely in the print media, but also (in full color) on postcards as well. At the same time, talented illustrators and cartoonists back home also threw their talents into this new enterprise of international reportage and commentary.

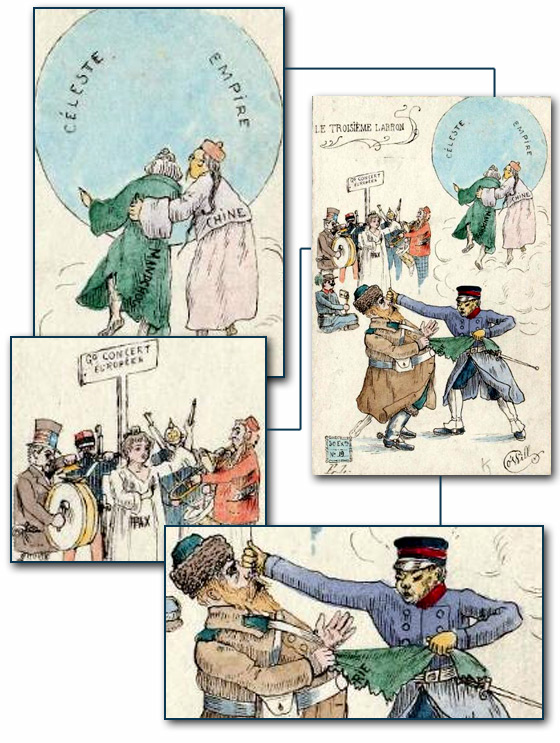

One of the small ironies of this well-watched war was that it was observed most keenly outside the territories the two armies were fighting over—Korea and Manchuria in the northernmost part of China. Unlike Japan, neither Korea nor China had responded successfully to the challenge of the more technologically advanced Western world. They were going under, and lacked the infrastructure necessary to participate in this new world of mass communication. A French postcard of the war captures this situation almost inadvertently: while Russia and Japan fight it out and the Western world looks on as rapt spectators, the old “celestial empire” (here “China” and “Manchuria” in traditional garb) flees from the scene. Apart from the Japanese, other Asians were not churning out photographs and postcards for a national or international audience.

|

|

In this French postcard rendering of the well-watched Russo-Japanese War, the peaceful nations of Europe observe Russia and Japan fighting, while the now powerless “celestial empire” (China and Manchuria) withdraws from the scene. In this French postcard rendering of the well-watched Russo-Japanese War, the peaceful nations of Europe observe Russia and Japan fighting, while the now powerless “celestial empire” (China and Manchuria) withdraws from the scene.

[2002.6801]

|

The postcards in particular changed the way large numbers of people saw the world. They ranged from “realistic” to highly subjective, and they crossed national borders with remarkable ease. Pictures transcended language per se; and where language mattered, in the form of captions, entrepreneurs quickly learned how to cater to an international audience. The same postcard might appear in different languages, for example, or with the caption given in multiple languages (usually three or seven) on a single card.

Manufacturers of picture postcards also cultivated a clientele of international collectors. Cards might be issued in a numbered series featuring a common theme or artistic style, for instance. They might also involve a kind of comic-strip unfolding, in which it took two or more cards to play out a story line. Both foreign and Japanese postcards of the Russo-Japanese War were creative in this regard, and the foreign illustrators were particularly keen (and cynical) when it came to placing the war in a broader context of power politics among the great imperialist nations.

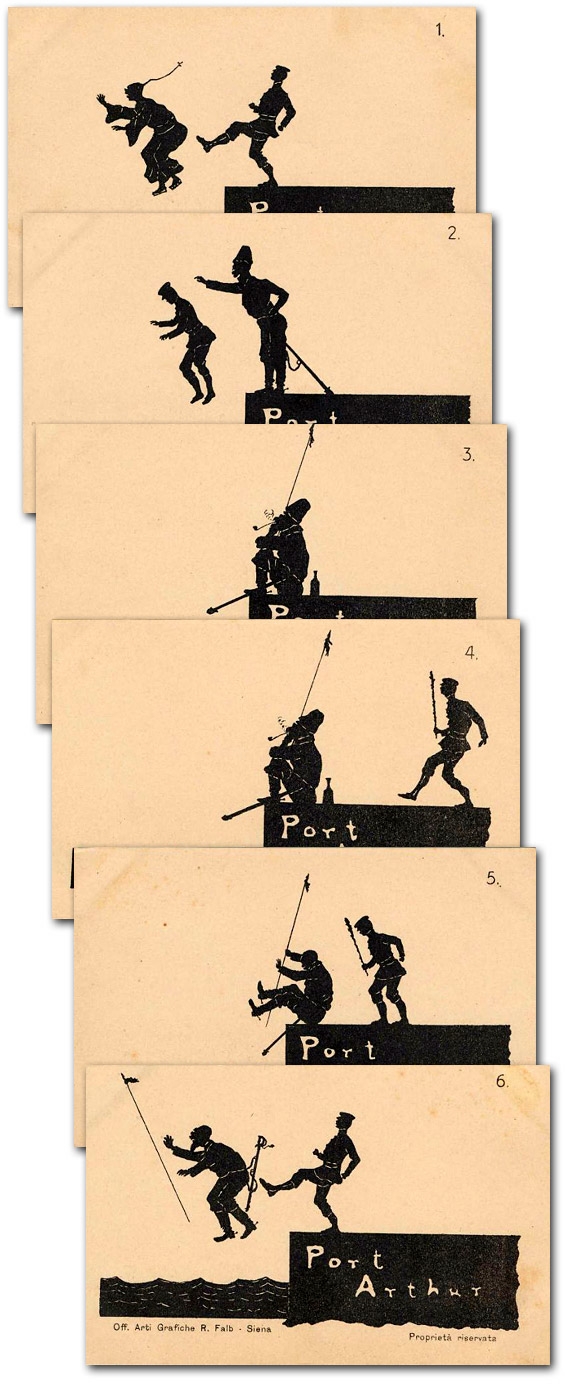

One of the liveliest “historical” sequences in this regard, for example, is a six-card run produced in Italy that requires no Italian whatsoever to understand. The setting is “Port Arthur,” where the Japanese navy initiated war in February 1904 with a surprise attack on the Russian Far Eastern fleet. The picture sequence, done as simple black woodcut “silhouettes,” begins with the Japanese kicking the Chinese out of that strategic port (in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95). Russia then kicks the Japanese out (the reference is to the so-called Triple Intervention of 1895) and settles into Port Arthur for a while itself (referring to 1898–1904). The final three graphics depict the Japanese sneaking up upon the Russians; giving them a blow from behind (the surprise attack); and, finally, kicking the Russians out just as they had done to the Chinese 10 years (and five postcards) earlier.

|

|

This Italian set of cards offers an ironic historical resume of power politics focusing on the strategic military base of Port Arthur between 1894 and 1904. (Port Arthur provided critical access to China, Manchuria, and Korea and was key to control of the surrounding seas.) In this sequence, (1) Japan kicks out China in 1894, (2) Russia shoves out Japan in 1895, (3) Russia occupies Port Arthur and the Liaotung Peninsula from 1898 to 1904, (4) the Japanese sneak back in 1904, (5) clobber the Russians in a surprise attack, and (6) kick the Russians out. This Italian set of cards offers an ironic historical resume of power politics focusing on the strategic military base of Port Arthur between 1894 and 1904. (Port Arthur provided critical access to China, Manchuria, and Korea and was key to control of the surrounding seas.) In this sequence, (1) Japan kicks out China in 1894, (2) Russia shoves out Japan in 1895, (3) Russia occupies Port Arthur and the Liaotung Peninsula from 1898 to 1904, (4) the Japanese sneak back in 1904, (5) clobber the Russians in a surprise attack, and (6) kick the Russians out.

[2002.6771] through [2002.6776]

|

A nice example of sardonic foreign commentary on the power politics of the war—and, simultaneously, a good example of the manner in which these graphics jumped national borders—emerges in a pair of postcards, one in German and the other in French, that obviously derive from the same artist and original source. The first (in German) devotes half of the graphic to a detailed map of Korea and Manchuria, where the fighting took place. The Russian bear, with a French cap hanging on its stubby tail, confronts a female figure representing Japan (her theatrical costume is more Chinese than Japanese) behind whom stands an Englishman with a battleship on his head murmuring “Yessss… Allright!”

|

![The Russo-Japanese War Artist unknown [2002_5144] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston](image/2002_5144_s.jpg) |

“The Russo-Japanese War”

[2002.5144]

|

This German postcard combines a map with humorous commentary on strategic

alliances that lay behind the war. Russia (the bear) is backed up by France

(a French hat on the bear’s tail), while Britain (with a warship on its head,

reflecting the Anglo-Japanese naval alliance) stands behind feminine Japan. This German postcard combines a map with humorous commentary on strategic

alliances that lay behind the war. Russia (the bear) is backed up by France

(a French hat on the bear’s tail), while Britain (with a warship on its head,

reflecting the Anglo-Japanese naval alliance) stands behind feminine Japan.

|

The German graphic is droll (so much so, indeed, that one suspects that it was probably not German in origin). A companion postcard in French depicting the end of the war has both sides bloodied and battered, blood trailing and vultures descending behind them, still backed up by their great-power supporters (France is now represented by a Joan-of-Arc figure in armor). Despite a succession of Japanese victories on sea and land, the brutal war did actually end in near stalemate, with both sides deep in debt and close to exhaustion. This is not, however, an image that one finds in Japanese postcard representations of the conflict, which tended to be overwhelmingly celebratory.

|

“End of

the War”

[2002.3762]

|

![End of the War Artist unknown [2002_3762] Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Museum of Fine Arts Boston](image/2002_3762_s.jpg) |

This French rendering of the war’s bloody end appears to come from the same series as the preceding German postcard. Both Russia and Japan have been severely battered and fallen deep in debt. Their allies (and creditors) look on with concern, while vultures feast on the carnage. This French rendering of the war’s bloody end appears to come from the same series as the preceding German postcard. Both Russia and Japan have been severely battered and fallen deep in debt. Their allies (and creditors) look on with concern, while vultures feast on the carnage.

|

Postcards with the caption given in multiple languages commonly involve painterly and highly dramatic battlefront scenes. Here are representative examples from a sophisticated series printed with seven languages: Japanese, Russian, French, Italian, English, German, and Spanish.

|

|

Multi-language postcards included this sophisticated seven-language series, which carried captions in Japanese, Russian, French, Italian, English, German, and Spanish. The country of origin is unclear, but the artistic style is clearly European rather than Japanese. Multi-language postcards included this sophisticated seven-language series, which carried captions in Japanese, Russian, French, Italian, English, German, and Spanish. The country of origin is unclear, but the artistic style is clearly European rather than Japanese.

Two of the great battles of the war are depicted—Admiral Markaroff recoiling on the deck of his flagship, which sank with few survivors in the decisive 1905 Battle of Tsushima; and early stages of the ferocious battle of Mukden, which pitted over 300,000 Russians against a quarter-million Japanese and ended in Japanese victory.

“Death of Admiral Makaroff”

[2002.3979]

“The Battle of Mukden in Manchuria in 1904”

[2002.3982]

|

A typical three-language (French, German, English) series includes detached and unbiased illustrations such as the following:

|

|

The trans-national audience for war postcards also emerges explicitly in this three-language series, where the caption is written in French, German, and English. The trans-national audience for war postcards also emerges explicitly in this three-language series, where the caption is written in French, German, and English.

“The Japanese Army Crossing the Jho [Iho] River”

[2002.3967]

“Battle of Chemulpo; the Sinking of the Korejec”

[2002.3971]

|

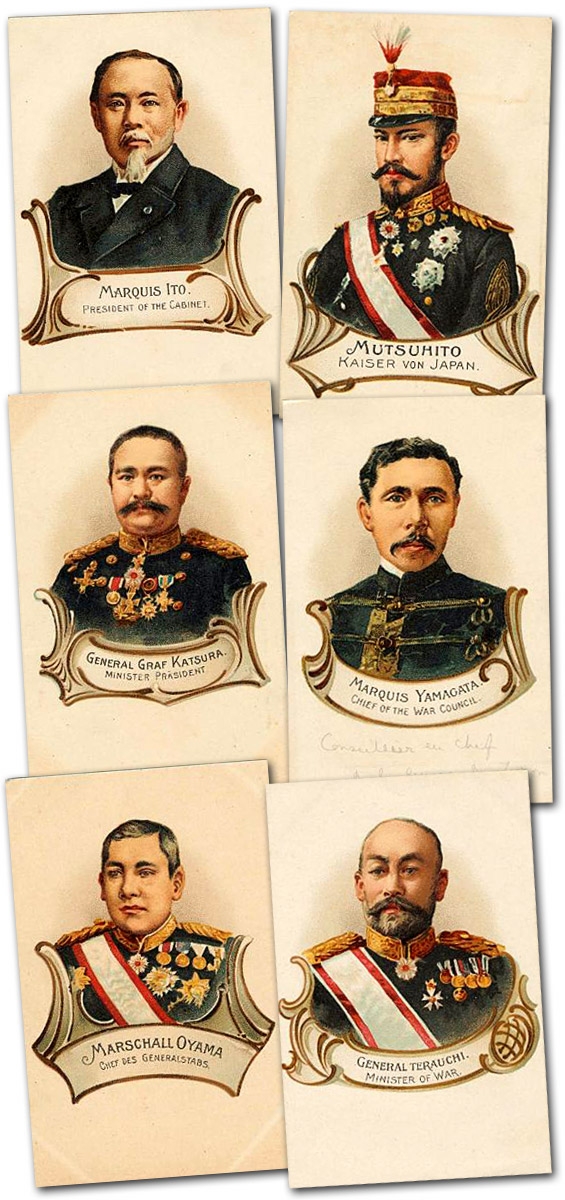

There also existed a European and English-speaking audience for postcards featuring formal portraits of Japanese and Russian leaders. Again, the country of origin is often difficult to identify, for the same set might appear in different languages, as in the following series featuring both German and English versions:

|

|

This portrait series of Japan’s most famous military and civilian leaders (including Mutsuhito, the Meiji emperor) appeared in both English and German versions. In these flattering treatments, the Japanese are virtually indistinguishable from European and British dignitaries. This portrait series of Japan’s most famous military and civilian leaders (including Mutsuhito, the Meiji emperor) appeared in both English and German versions. In these flattering treatments, the Japanese are virtually indistinguishable from European and British dignitaries.

“Marquis Ito, President of the Cabinet”

[2002.5554]

“Mutsuhito, Emperor of Japan”

[2002.5553]

“General Count Katsura, Prime Minister”

[2002.3681]

“Marquis Yamagata, Chief of the War Council”

[2002.5551]

“Marshal Oyama, Chief of the General Staff”

[2002.3682]

“General Terauchi, Minister of War”

[2002.5549]

|

The dignity and respect with which these eminent Japanese are portrayed is noteworthy: they are treated as leaders of a great nation, no different from Western dignitaries. A French portrait series in which Japanese leaders were often paired with their Russian counterparts on a single postcard follows this even-handed approach:

|

|

In this stylish French series, paired portraits of Russian and Japanese military leaders highlight their dignity and similarity. In this stylish French series, paired portraits of Russian and Japanese military leaders highlight their dignity and similarity.

“Russian General Stoessel and Japanese General Terauchi”

[2002.3672]

“Russian General Kuropatkin and Japanese General Kodama”

[2002.3666]

|

As will be seen, however, such complimentary “mirror images” were far from an invariable rule. The outpouring of foreign postcards of the Russo-Japanese War can indeed be used to illustrate the Western world’s acceptance and even admiration of Japan’s remarkably swift emergence as a powerful modern state. Just as often, however, these graphics also tell an entirely different story. Sometimes the mirror images are mutually derogatory. For every positive representation of the Japanese in particular, moreover, there is a negative one. On the one hand, Japan represents the promise of a modernizing Asia; on the other hand, the Japanese are presented as exotic upstarts, blood-soaked aggressors, the vanguard of a “Yellow Peril” that threatens Western civilization itself.

|

|

|