| |

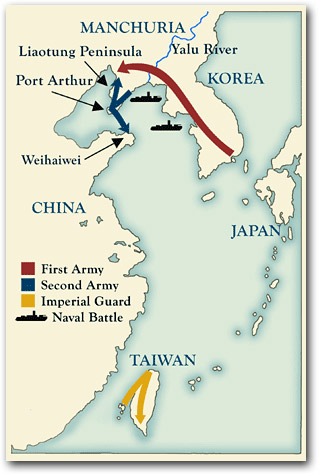

The Sino-Japanese War began in July 1894 and ended in China’s shattering defeat in April 1895. It involved battles on land and sea; began with fighting in Korea that spilled over the Yalu River into Manchuria; witnessed the opening of a second front on the Liaotung (Liaodong)

Japanese lines of attack in the

Sino-Japanese War

(July 1894–April 1895)

|

Peninsula and against Chinese fortifications at Weihaiwei as well as Port Arthur; and eventually involved a Japanese assault on the distant Chinese island of Formosa (Taiwan).

On the Japanese side, approximately 240,000 fighting men were mobilized for the campaigns in Korea and China proper, along with another 154,000 behind-the-lines laborers. Battlefield fatalities were surprisingly low, numbering only around 1,400; additionally, many died of illnesses, particularly those caused by severe winter conditions. Another 50,000 troops and 26,000 laborers were deployed in the relatively ignored Formosa campaign, where Japanese losses were actually higher. Overall Chinese casualties were much greater. In the battle for Port Arthur alone, for example, it is estimated that as many as 60,000 Chinese, including civilians, may have been killed.

In this moment of heady triumph, Japan did indeed seem to have “thrown off Asia” and gained recognition as a modern power, just as Fukuzawa had urged more than a decade earlier. This great demonstration of military prowess not only hastened the end of the unequal treaties that the foreign powers had saddled Japan with ever since the 1850s. It also opened the door to an extraordinary, almost unimaginable prize: the conclusion (in 1902) of a bilateral military alliance with Great Britain.

As time would show, however, this proved a costly triumph for everyone involved. In taking the imperialist powers as a model even while condemning their arrogance and aggression, the Japanese had adopted an inherently ambiguous and contradictory role. And in “throwing off” China as they did—not merely decisively but also derisively—they exhibited a racist contempt for other Asians that, even today, can take one’s breath away.

Lafcadio Hearn, the distinguished writer and long-time resident of Japan, immediately recognized the perilous nature of the new world Japan had entered. In 1896, the year after the war ended, he wrote this:

|

The real birthday of the new Japan … began with the conquest of China. The war is ended; the future, though clouded, seems big with promise; and, however grim the obstacles to loftier and more enduring achievements, Japan has neither fears nor doubts. The real birthday of the new Japan … began with the conquest of China. The war is ended; the future, though clouded, seems big with promise; and, however grim the obstacles to loftier and more enduring achievements, Japan has neither fears nor doubts.

Perhaps the future danger is just in this immense self-confidence. It is not a new feeling created by victory. It is a race feeling, which repeated triumphs have served only to strengthen.

(Quoted from Hearn’s book Kokoro by Shumpei Okamoto in Impressions of the Front.)

|

Nothing reveals this “race feeling” more graphically than the lively woodblock prints through which Japanese on the home front visualized—and grew rapturous over—what was taking place.

Although the Sino-Japanese War lasted less than a year, woodblock artists churned out around 3,000 works of ostensible battlefront “reportage”—amounting, as Donald Keene has pointed out, to an amazing ten new images every day.

This was not “high art.” The woodblock print itself was a popular art form that dated back only to the 17th century and found its audience in an emerging class of ordinary city dwellers. The prints were neither costly nor meant to be cherished and preserved as timeless creations. They were designed to amuse and entertain—and to introduce an untidy mass audience to worlds of hitherto unimagined beauty and fascination, whether this be courtesans and actors in the pleasure quarters, or places the print viewer might never personally see, or purely imagined realms of heroes, villains, ghosts, grotesqueries, and erotic indulgence. In subject, style, and audience, the exuberant woodblock prints were the antithesis of most things associated with tasteful upper-class classical art.

What we now regard as the great flowering of the woodblock-print tradition ended at the very end of the feudal era with artists of surpassing genius such as Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858). The “Meiji prints” that followed were less esteemed. Even generations later, after collectors and connoisseurs had belatedly come to recognize the enormous creativity and enduring value of the feudal-era prints—had accorded them, as it were, a kind of “classic” stature of their own—the prints of the modern era were generally held in low regard.

It is only in recent decades that the Meiji prints have drawn serious attention. Partly, it must be acknowledged, this came about because they were lying around in considerable quantity and much less expensive to collect than the suddenly pricey feudal prints. Partly, too, this rise in interest occurred because these later prints were belatedly seen to have a distinctive vigor all their own.

There was, however, a third factor behind the rediscovery of Meiji prints. As historians began to turn increasing attention to “popular” culture (beginning around the 1960s), and to place more weight on studying “texts” that went beyond written documents per se, graphics and images of every sort were suddenly recognized to be a vivacious way of visualizing the past. One could, in effect, literally see what people in other times and places were themselves actually seeing—and then try to make sense of this. One could “read” visual images much as one might read the written word—not simply as art, but also as social and cultural documents.

In the decades following Perry and the opening of Japan, woodblock prints became a major vehicle for presenting a picture of current affairs. When foreigners first came to the newly-opened treaty port of Yokohama in the early 1860s, for example, it was the woodblock artists who seized this opportunity to churn out “Yokohama prints” that purported to show how the Westerners lived. If we wish to see how Japanese at the time visualized the upheaval that culminated in the Meiji Restoration itself, or how they pictured the vogue of Westernization that followed in the 1870s and 1880s, there is no more vivid source, once again, than these popular prints.

|

|

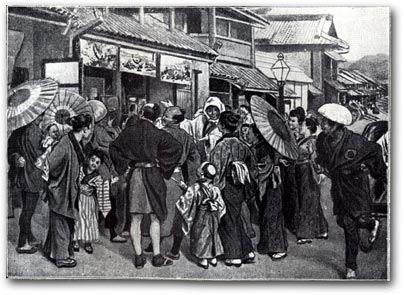

A crowd views war prints displayed at a publisher’s shop. Although dating from 1904, this western etching captures the scale of the woodblock prints and one of the primary ways in which they were seen by a wide audience in Japan.

From Japan’s Fight for Freedom, part III (1904), p. 74.

|

Similarly, it is to the modern woodblock prints that we now turn to recapture a sense of the emotional popular support that accompanied Japan’s emergence as an aggressive, expansionist power at the end of the 19th century. Nationalism, militarism, imperialism, a new sense of cultural and even racial identity—all found their most flamboyant expression here. Indeed, the popular prints did not merely “capture” this sentiment; they played a role in pumping it up. They are the most dramatic and easily accessible source we have for getting a “feel” for the redefinition of national identity that went hand-in-hand with Japan’s debut as a major power.

In the West, the “journalistic” role that woodblock prints played in late-19th-century Japan was largely filled by publications that featured engravings and lithographs based on photographs. By the time of the Sino-Japanese War, popular periodicals such as the Illustrated London News also featured photographs themselves. The impression of the world these Western graphics conveyed was, as a rule, both more “realistic” and more detached. They were literally, and often figuratively as well, colorless—a sharp contrast to the vivacious and highly subjective woodblock prints.

Japanese photographers did cover the Sino-Japanese War; an evocative woodblock by Kobayashi Kiyochika even takes them as its subject, standing in the snow and photographing the troops with a large box camera on a tripod.

|

![Illustration of Photographing Our Troops Fighting in the Fortress Town Niuzhuang by Kobayashi Kiyochika, April 1895 [2000_473] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_473_det_s.jpg) |

“Illustration of Photographing Our Troops Fighting in the Fortress Town Niuzhuang” (detail) by Kobayashi Kiyochika, April 1895

[2000.473] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

It was only after this war, however, that photography entered the pages of Japanese newspapers and magazines in a substantial way. Until then, the woodblock illustrations held center stage as graphic “reportage.” The Sino-Japanese War marked the apogee of this phenomenon—the unquestioned high point of Meiji woodblock art. War prints were the most vivid, dramatic, emotional medium through which Japanese on the home front could follow—almost literally day-by-day—the momentous conflict on the other side of the Yellow Sea.

There was no counterpart to this on the Chinese side—no such popular artwork, no such explosion of nationalism, no such nation-wide audience ravenous for news from the front.

As it happens, there does exist a rare, anonymous Japanese woodcut engraving of one of the greatest battles of the Sino-Japanese War, the capture of Port Arthur in November 1894. Identical in size with a standard-size woodblock triptych (14 x 28 inches), this suggests how Japanese graphic artists might have depicted the war if they had adopted the Western practice of detailed black-and-white renderings. The detail is, indeed, meticulous—so obsessively fine that the overall impression is almost clinical. The contrast to the animated multi-colored woodblock prints could hardly be greater.

|

![Illustration of the Second Army Attacking and Occupying Port Arthur, artist unknown, late 18941895 [2000_369] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_369_s.jpg) |

![Illustration of the Second Army Attacking and Occupying Port Arthur, artist unknown, late 18941895 (detail)[2000_369] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_369_s_det01.jpg) |

A rare Japanese woodcut engraving of the

Sino-Japanese War.

“Illustration of the Second Army Attacking and Occupying Port Arthur,” artist unknown, 1894

[2000.369] Sharf Collection,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

![Illustration of the Second Army Attacking and Occupying Port Arthur, artist unknown, late 18941895 (detail) [2000_369] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_369_s_det03.jpg) |

|

A well-known print by Mizuno Toshikata depicting a battle in July 1894 suggests many of the conventions that came to distinguish the Sino-Japanese War prints in general. This was the opening stage of the war, and the print’s title alone conveys the fever pitch of Japanese nationalism: “Hurrah, Hurrah for the Great Japanese Empire! [Dai Nihon Teikoku Ban-Banzai!] Picture of the Assault on Songhwan, a Great Victory for Our Troops.”

|

![Hurrah, Hurrah for the Great Japanese Empire! Picture of the Assault on Songhwan, a Great Victory for Our Troops by Mizuno Toshikata, July 1894 [2000_435] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_435_s.jpg) |

“Hurrah, Hurrah for the Great

Japanese Empire! Picture of the

Assault on Songhwan, a Great

Victory for Our Troops” by

Mizuno Toshikata, July 1894 (above)

[2000.435] Sharf Collection,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Although a few artists accompanied Japanese journalists to the battlefront, as seen in this detail (right), the woodblock artists stayed in Japan. Their war prints were largely imaginative creations based on news reports.

|

![Hurrah, Hurrah for the Great Japanese Empire! Picture of the Assault on Songhwan, a Great Victory for Our Troops by Mizuno Toshikata, July 1894 (detail) [2000_435] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_435_det.jpg) |

In Toshikata’s rendering, stalwart Japanese soldiers with a huge “Rising Sun” military flag in their midst advance against a Chinese force in utter disarray. Can we trust the veracity of this artistic rendering? Surely we can, for on the right-hand side of Toshikata’s print we see a delegation of Japanese “newspaper correspondents” that includes at its head not one but two artists, identified by name. Depictions such as this very print, Toshikata seems to be assuring his audience—and right at the start of the war—could be trusted to be accurate.

The overwhelming majority of war prints were, in fact, nothing of the sort. Although some artists and illustrators did travel with the troops, the woodblock artists remained in Japan—catching the latest reports from the front as they came in by telegraph and rushing to draw, cut, print, display, and sell their pictured version of what they had read before this particular “news” became outdated. (Occasionally prints were initiated in anticipation of the actual event!) Toshikata was offering an imagined scene—a set piece that quickly became formulaic.

In these circumstances, prints often simply “quoted” other prints. In early November 1894, for example, Toshikata’s colleague Watanabe Nobukazu produced a rendering of “Our Forces’ Great Victory and Occupation of Jiuliancheng” that bore close resemblance to Toshikata’s “Hurrah, Hurrah” of over three months earlier. Disciplined soldiers looked down from on high, other troops advancing below them. The same military flag fluttered in the same right hand panel of the triptych; a bent and gnarled pine, so beloved in Japanese art, was again rooted in the center of the image; the foe retreated in the far distance.

|

![Our Forces Great Victory and Occupation of Jiuliancheng by Watanabe Nobukazu, November 1894 [2000_380_37] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_380_37_s.jpg) |

“Our Forces’ Great Victory and Occupation of Jiuliancheng” “Our Forces’ Great Victory and Occupation of Jiuliancheng”

by Watanabe Nobukazu, November 1894

[2000.380.37] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

That same November, Ogata Gekkō used much the same flag, pine, and craggy bluff to illustrate the army’s advance on Mukden.

|

![Picture of the First Army Advancing on Fengtienfu by Ogata Gekkō, November 1894 [2000_409] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_409_s.jpg) |

“Picture of the First Army Advancing on Fengtienfu” “Picture of the First Army Advancing on Fengtienfu”

by Ogata Gekkō, November 1894

[2000.409] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

The heroic officer in Toshikata’s “Hurrah, Hurrah” print, striking a dramatic pose with his sword held high, also quickly became a stock figure. He might have stepped out of a Kabuki play (or a traditional print of a Kabuki actor or legendary warrior)—and certainly did step into a great many other scenes from the Sino-Japanese War.

|

![Detail of heroic officer from Hurrah, Hurrah for the Great Japanese Empire! Picture of the Assault on Songhwan, a Great Victory for Our Troops by Mizuno Toshikata, July 1894 [2000_435] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_435_popout.jpg) |

Detail of heroic officer in “Hurrah, Hurrah for the Great Japanese Empire! Picture of the Assault on Songhwan, a Great Victory for Our Troops” by Mizuno Toshikata, July 1894 Detail of heroic officer in “Hurrah, Hurrah for the Great Japanese Empire! Picture of the Assault on Songhwan, a Great Victory for Our Troops” by Mizuno Toshikata, July 1894

[2000.435] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

Toshikata himself introduced virtually the identical hero under many different—and always real—names in his war prints. (His Japanese fighting men almost always were in movement from right to left, as if the print were a map and the viewer eye-witness to Japan’s westward advance onto the continent. This overlapped, of course, with the conventional right-to-left movement of writing and reading, and conventional unfolding picture scrolls.) Toshikata’s archetypical hero appeared, for example, as “Lieutenant Commander Sakamoto” on the warship Akagi; as “the skillful Harada Jūkichi” in the attack on Hyonmu Gate (the sword here turned into a bayonet); as “Captain Matsuzaki” in the battle of Ansong Ford; and as “Captain Higuchi” in a near mythic battle at the “Hundred-Foot Cliff” near Weihaiwei (see details below).

The same Captain Higuchi—flourishing his sword and leading his forces in attack while clutching a Chinese child found abandoned on the battlefield—steps into a print by Migita Toshihide in almost the identical heroic pose. Even the horizontal lines that streak across the scene to suggest gunfire appear in both prints. When Toshihide depicts “Colonel Satō” in an entirely different battle, he essentially just turns his Captain Higuchi in the opposite direction and has him braving the bullets while holding a flag instead of a child. Later, when the Japanese army moved south to occupy the Pescadores, Toshihide’s intrepid officer metamorphosed as “Captain Sakuma raising a war cry”. Gekkō’s version of the bearded “Colonel Satō charging at the enemy” turned the hero back to the usual charging-left direction. Ginkō placed his intrepid hero-with-a-sword (in this case, unnamed) on horseback in his rendering of the great battle of Pyongyang.

|

The Predictable Pose of the Hero

Although prints of the Sino-Japanese War purported to depict actual battles and the exploits of real-life officers and enlisted men, the “Hero” almost invariably struck a familiar pose—like a traditional Kabuki actor playing a modern-day warrior. Officers in austere Western-style uniforms brandished swords (the counterpart for enlisted men was the bayonet). Their posture was resolute, their discipline obvious, their will transparently unshakable.

|

!["The Great Battle of Ansong Ford: The Valor of Captain Matsuzaki" by Mizuno Toshikata, 18.... (detail) [2000_115] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_115_g.jpg) |

!["The Skillful Harada Jūkichi of the First Army in the Attack on Hyonmu Gate Leads the Fierce Fight" by Mizuno Toshikata, 18.... (detail) [2000_101] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_101_g.jpg) |

!["Lieutenant Commander Sakamoto of the Imperial Warship 'Akagi' Fights Bravely" by Mizuno Toshikata, 18.... (detail) [2000_380_20] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_380_20_g.jpg) |

“Captain Matsuzaki” “Captain Matsuzaki” |

“Harada Jūkichi” |

“Lt. Commander Sakamoto” |

!["Picture of Colonel Satō Attacking the Fortress at Niuzchuang" by Migita Toshihide, 18.... (detail) [2000_433] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_433_g.jpg) |

!["Captain Higuchi, the Battalion Commander of the Sixth Division...." by Migita Toshihide, 18.... (detail) [2000_427] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_427_g.jpg) |

!["Captain Higuchi" by Mizuno Toshikata, 18.... (detail) [2000_439] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_439_g.jpg)

|

“Colonel Satō” “Colonel Satō” |

“Captain Higuchi” |

“Captain Higuchi” |

![??????????????????????????????? (detail) [2000_380_02] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_380_02_g.jpg) |

![????????????????????????????????? (detail) [2000_182] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_182_g.jpg) |

!["Picture of Captain Sakuma Raising a War Cry at the Occupation of the Pescadores" by Migita Toshihide, 18.... (detail) [2000_134] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_134_g.jpg) |

unidentified officer unidentified officer |

“Colonel Satō” |

“Captain Sakuma” |

|

|

|

|

|

Much of the appeal of the prints to Japanese on the home front resided in predictability of this sort—much like seeing the same theatrical play staged and performed by different directors and actors. Repetition is reassuring. Comfort lies in the familiar—not just recognizable posturing, but the larger formulaic melodrama of heroic struggle and rousing triumph. Sometimes the print even became a crowded stage in which the artist literally threw a spotlight (here a searchlight) on the disciplined Japanese annihilation of archaic China. A dramatic “searchlight” print by Toshimitsu of “Our Army’s Great Victory at the Night Battle of Pyongyang,” is a typical example of this.

|

![Our Armys Great Victory at the Night Battle of Pyongyang by Kobayashi Toshimitsu, September 1894 [2000_051] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_051_s.jpg) |

“Our Army’s Great Victory at the Night Battle of Pyongyang” “Our Army’s Great Victory at the Night Battle of Pyongyang”

by Kobayashi Toshimitsu, September 1894

[2000.051] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

As these prints make clear, the other side of stirring triumphalism was thoroughgoing defeat of the enemy. This, too, followed predictable patterns: the Chinese foe overwhelmed and in disarray, smashed to the ground and sent flying through the air, lying dead as rag dolls on the ground—often but half seen, or half buried in snow.

|

Routing the Foe

While Japanese fighting men were invariably depicted as heroic, renderings of the Chinese foe also followed predictable patterns. Their brightly colored, old-fashioned garments posed a sharp contrast to the austere Western-style uniforms of the Japanese, and they were commonly depicted as being overwhelmed, routed, and slaughtered. Such images graphically captured the double implications of “Throwing off Asia” rhetoric: first, getting rid of old-fashioned and non-Western attitudes, customs, and behavior in Japan itself; and second, literally overcoming Japan's Asian neighbors, who were perceived as having failed to respond to the Western challenge, and thereby imperiling the security of all Asia. Such attitudes reflected the survival-of-the-fittest ideas that the Japanese learned from the Western powers themselves.

|

“The Skillful Harada Jūkichi of the First Army in the Attack on Hyonmu Gate Leads the Fierce Fight” (detail) by Mizuno Toshikata, October 1894

[2000.101] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

![The Skillful Harada Jūkichi of the First Army in the Attack of Hyonmu Gate (Genbumon) Leads the Fierce Fight by Mizuno Toshikata, October 1894 (detail) [2000_101] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_101_det_vic.jpg)

|

![Picture of Colonel Satō Attacking the Fortress at Niuzhuang by Migata Toshihide, 1894 (detail) [2000_433] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston](../throwing_off_asia_01/image/2000_433_snow.jpg) |

“Picture of Colonel Satō Attacking the Fortress at Niuzhuang” (detail) by Migata Toshihide, 1894

[2000.433] Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

|

|

|

|

|

Clothing, too, rendered the two sides as different as night and day. In contrast to the disciplined Japanese fighting men in their somber Western-style uniforms, the Chinese wear loose garments in almost riotous colors. They appear strange, old-fashioned, almost picturesque—trapped in a time warp and certainly out of place in a modern war. Japan’s heroes are up-to-date—always moving as a disciplined unit, but at the same time frequently singled out by name. The Chinese, with very few exceptions, emerge as a disorderly mass redolent of a backward and bygone time.

There is nothing unique about valorizing and personalizing one’s own side while diminishing the enemy. In the Sino-Japanese War, however, the Japanese were encountering war in unfamiliar ways. To begin with, although they possessed a deep history of warrior rule dating back to the late-12th century, this had actually ended with several centuries of peace. From the early-17th century until the arrival of Commodore Perry in the 1850s, Japan’s samurai elite had been warriors without wars.

Story-tellers and actors and artists in late-19th-century Japan thus had a rich tradition and repository of images concerning medieval warfare to draw upon—but no major recent wars apart from domestic conflicts just before and after the Meiji Restoration. The long Tokugawa period (1600–1868) that preceded the Restoration produced famous swordsmen rather than battlefield heroes. Beyond this, moreover, the “samurai” battlefield heroes of earlier times had come from a hereditary elite; there were few commoners among them.

The Sino-Japanese War thus provided something very new—not only real war and real battlefield heroes, and not only heroes from the lower ranks and lower classes, but also a modern and highly mechanized war against a foreign foe. Before the Restoration, Japan was not a “nation” per se. It did not define itself vis-à-vis other countries or interact in any serious way with them. The Restoration marked the real initiation of what we now call “nation building”—and the Sino-Japanese War carried this to an entirely new level. When Lafcadio Hearn spoke of the conquest of China as marking “the real birthday of the new Japan,” it was this sense of nationalistic—and now imperialistic—modernity that he had in mind.

There was tension, danger, huge risk in all this—and, certainly as the artists conveyed it, exhilarating beauty as well. Japan’s leaders threw the dice when they took on China in 1894. Indeed, most foreign observers initially assumed that China—with its rich history and vast size and population—would prevail. Instead, as the Japanese war correspondents and artists breathlessly conveyed to their fired-up audience back home, Japanese victories came swiftly. Chinese forces were routed. Japan had mastered modern war—not only on land, but also on the sea.

Most of the woodblock artists who tried to capture this excitement were young. (In 1894, when the war began, Kiyochika, the doyen of these artists, was 47 and Ogata Gekkō 35. Toshikata was 28, Toshihide 31, Taguchi Beisaku 30, Kokunimasa 22, Watanabe Nobukazu a mere 20. Toshimitsu’s birth date is unclear, but he was probably in his late 30s.) They not only imbibed the new nationalism, but seized the moment to introduce new artistic subjects (the weapons and machinery of modern war, explosions, searchlights, Asian enemies, real contemporary heroes in extremis)—and, with this, what they perceived to be a new Western-style sense of “realism” that extended beyond subject matter to new ways of rendering perspective, light, and shade.

When all was said and done, what they visualized in their propagandistic “war reportage” was a beautiful, heroic, modern war. For what turned out to be a fleeting moment, the woodblock artists imagined themselves to be splendidly up-to-date.

|

|

|