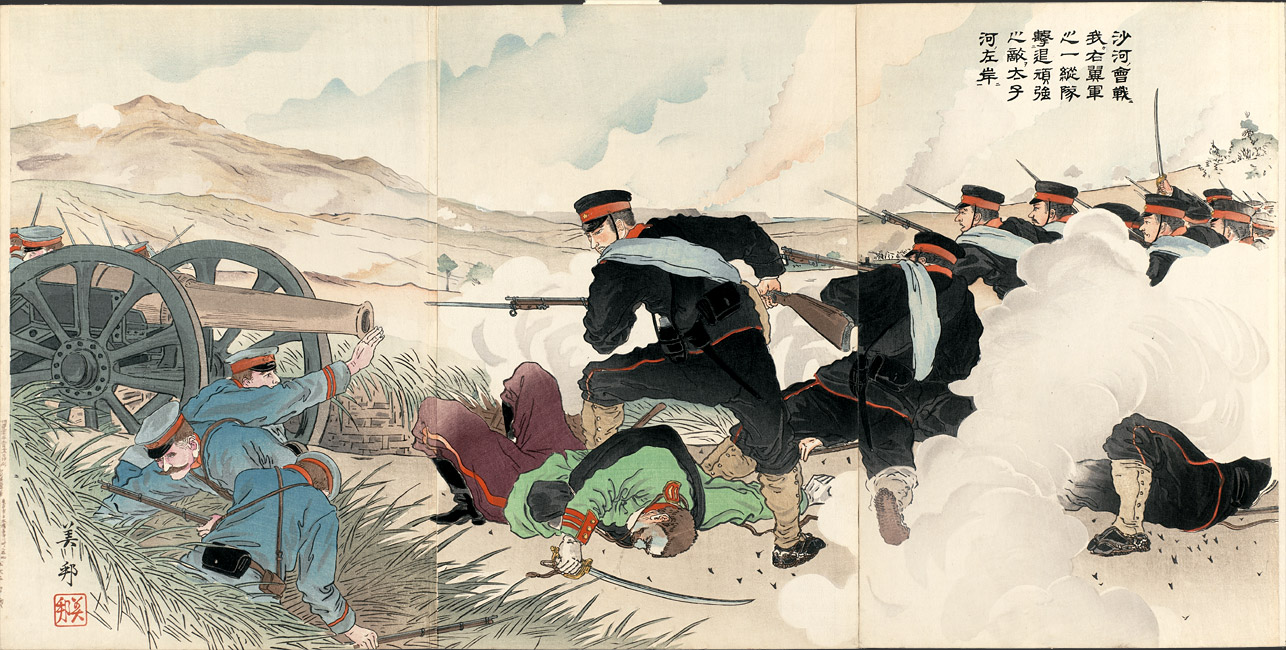

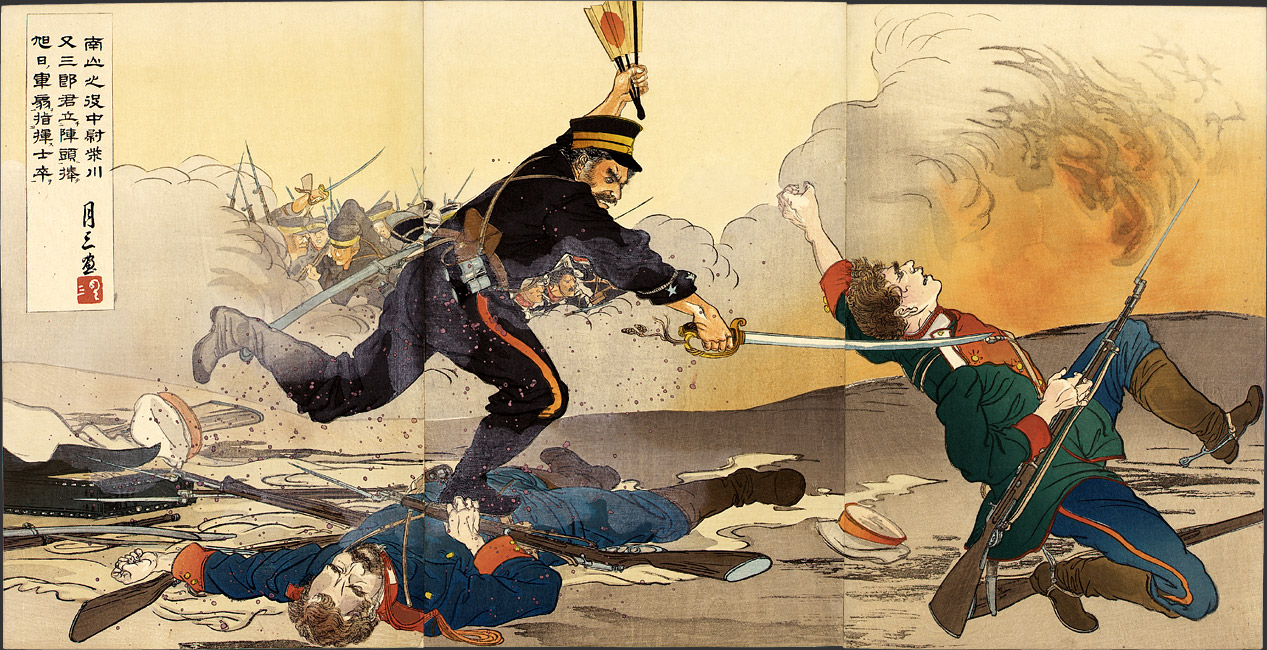

“In the Battle of the Sha River, a Company of Our Forces Drives a Strong Enemy Force

to the Left Bank of the Taizi River” by Yoshikuni, November 1904 [2000.472]

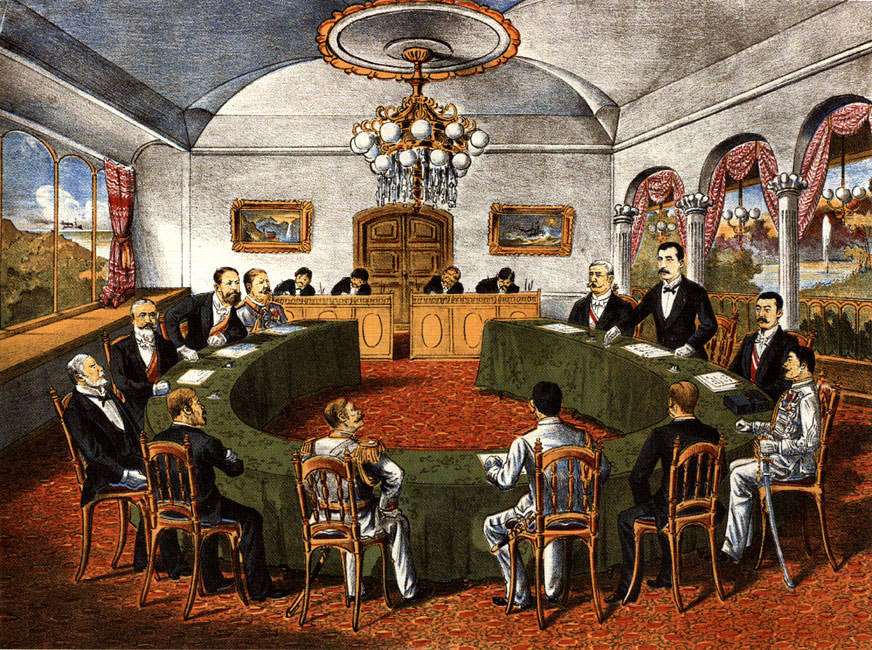

“The Battle of Liaoyang: The Enemy General Prince Kuropatkin, Having Tactical Difficulties and the

Whole Army Being Defeated, Bravely Came Forward into the Field to Do Bloody Battle” by Getsuzo, 1904 [2000.450]

This dramatic rendering of a Japanese officer striking down a Russian (while flourishing a battle fan used to signal orders) portrays the fallen foe as uncommonly handsome, even noble.

“In the Battle of Nanshan Our Troops Took Advantage of a Violent Thunderstorm

and Charged the Enemy Fortress” by Kobayashi Kiyochika, 1904 [2000.077]

Perhaps the single most gallant Japanese print produced during the Russo-Japanese War is this depiction of the famous Russian general Prince Kuropatkin, whom the Japanese defeated in battle.

“Russo-Japanese War: Great Japan Red Cross Battlefield Hospital Treating Injured”

by Utagawa Kokunimasa, March 1904 [2000.367]

In this “Red Cross” scene, the artist contrasts Japan’s humane treatment of wounded Russians to the coarse behavior of Russians toward local civilians.

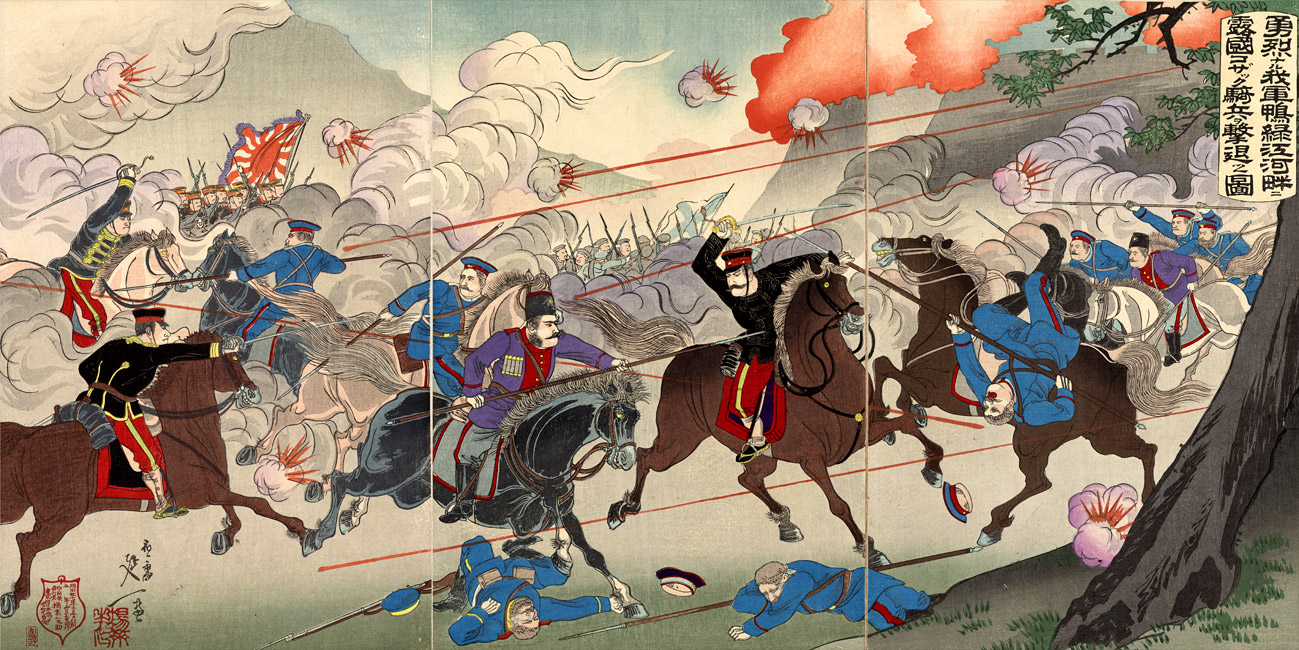

This congested battle scene features a heroic confrontation between cavalry officers, although the Russian side as a whole is being routed.

This early “fashion plate” of uniformed Russian and Japanese fighting men stresses the other side of the coin: basic similarities between the two sides.

The inset in Kiyochika’s battle scene typically depicts the essential similarities between officers on the two sides, even as the Russians concede Japanese victory.

“Illustration of Russian and Japanese Army and Navy Officers” by

Watanabe Nobukazu, February 1904 [2000.087]

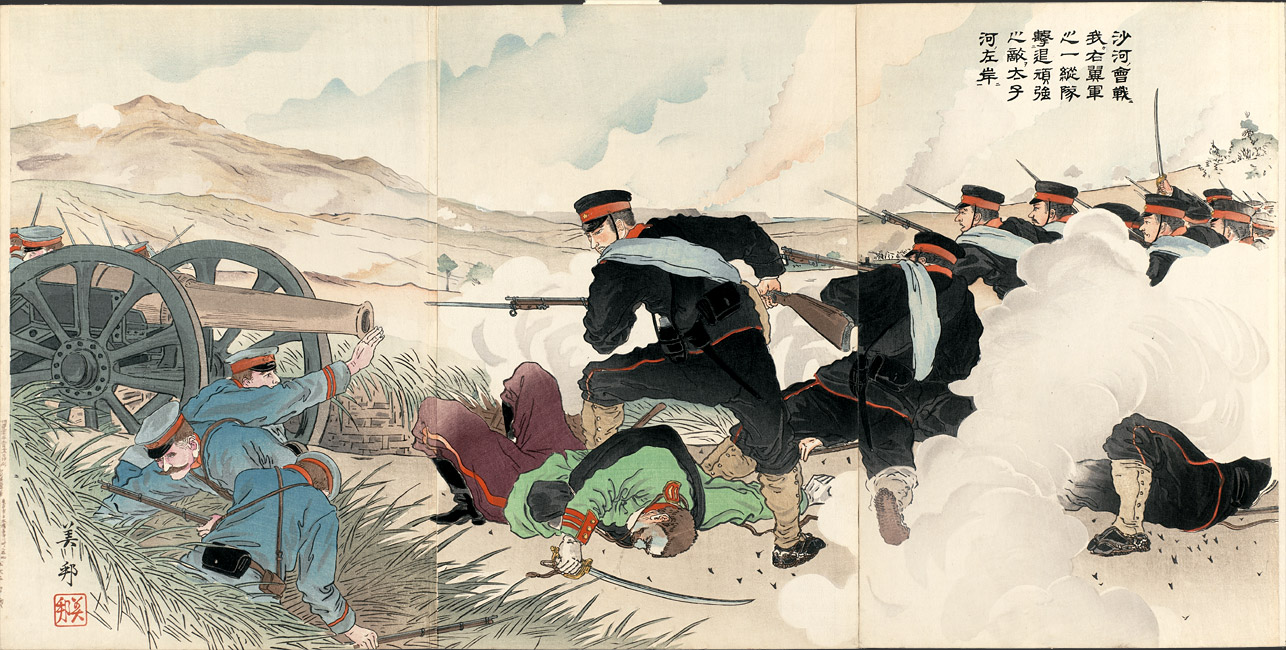

In this rare Japanese lithograph depicting the peace negotiations brokered by the United States in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the Japanese, Russians, and Anglo statesmen participating are almost indistinguishable. In Japanese eyes, the nation had finally succeeded in “throwing off Asia.”

“Picture of Our Valorous Military Repulsing the Russian Cossack Cavalry on the

Bank of the Yalu River” by Watanabe Nobukazu, March 1904 [2000.544]

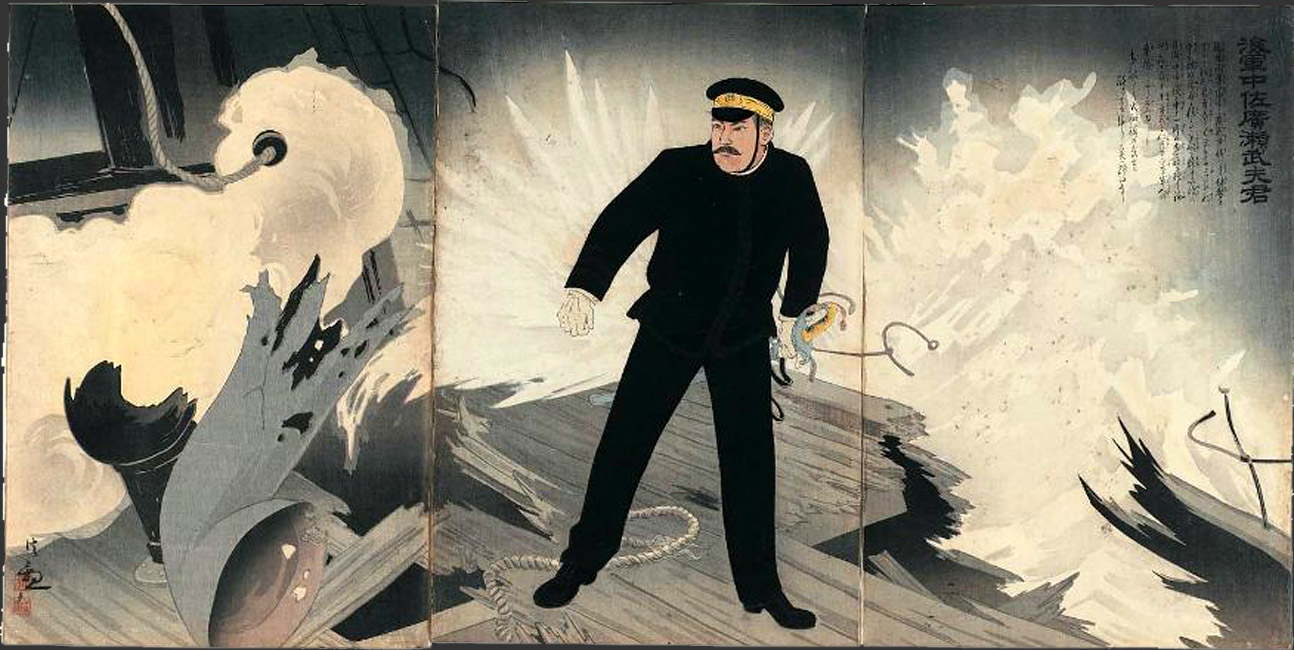

“Captain Hirose,” who perished while returning to find one of his missing men, was perhaps the single most celebrated Japanese hero in the Russo-Japanese War.

In the following print, the respectful treatment of the final moments of Russian vice-admiral Makarov, who went down with his ship along with 800 men, is every bit as tragic and poignant in its way as Captain Hirose’s death.

“In the Battle of Nanshan, Lieutenant Shibakawa Matasaburÿ Led His Men Holding up

a Rising Sun War Fan” by Getsuzo, 1904 [2000.448]

“A Great Victory for the Great Japanese Imperial Navy, Banzai! ” by Ikeda Terukata, April 1904

[2000.466]

“Negotiating Peace, Portsmouth, America”, artist unknown, August 1905

[toa5003] Private collection of Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf

“Navy Commander Hirose Takeo” by Kobayashi Kiyochika, 1904

[2000.542]