In the 1870s Japan emerged as a favorite destination for a new breed of tourist. Globetrotters, as they were called, arrived in the treaty ports in ever increasing numbers, stayed in new hotels built especially for them, visited scenic spots and famous places that they had read about in guidebooks, newspapers, or accounts written by other travelers, then moved on to other ports of call. Dozens of commercial photography studios boasting large inventories catered specifically to globetrotter tastes and sensibilities. Photographs bound in luxurious lacquer-covered albums became the most popular souvenirs globetrotters collected to memorialize their visits to Japan.

This site introduces the experience of

globetrotter travel to Japan and the commercial

photography business that was integral to it.

It reconstructs globetrotters’ experiences of

Japan through a selection of the most popular

scenic views and costumes of

the globetrotter era.

Primary sources in the form

of guidebooks and travel

accounts are used to explain

why the subjects depicted in

these photographs were so

central to the globetrotter

experience of Japan.

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

X

The Advent of Globetrotter Tourism

Thomas Cook, founder of the travel company that still bears his name, initiated the age of globetrotter tourism in the early 1870s when he led eight people on his first round-the-world tour. His group departed from Liverpool on September 26, 1872, steamed the Atlantic to New York, and then crossed North America by rail. From San Francisco they sailed to Yokohama, where they toured the sights of Tokyo before continuing by boat to Osaka and through the Inland Sea to Nagasaki. They visited Shanghai while en route to Singapore. From there they sailed to India, stopping briefly in Madras before disembarking in Calcutta for an extensive rail tour of the Indian subcontinent. Boarding a ship once again in Bombay, they sailed through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean. From there, they used well-established routes Cook had pioneered in the 1860s to return to England. It took 222 days to complete the entire journey.

Cook got his start in the travel business in the late 1840s organizing “Tartan Tours” of Scotland and excursions to the Lake District of England. He traveled with small enthusiastic groups, for which he personally negotiated excursions, transport, accommodation, and meals while en route. This business plan, which he used for all the routes he pioneered including his round-the-world venture, enabled Cook to scout viable excursions and establish new contacts he would need for future tours. Cook acquired a national profile as England’s premier travel service in 1851 by organizing inexpensive rail travel and accommodations for those wishing to visit the Great Exhibition in London. By the mid 1850s he was providing tours to various places in Europe. Egypt and Palestine emerged as popular and profitable destinations in the late 1860s.

Cook’s round the world tour of 1872 was made possible by several local developments in transportation networks. The initiation of regular service between San Francisco and Yokohama in 1867 made trans-Pacific crossings a regular affair. Completion of the Suez Canal in autumn 1869 made travel to S.E. Asia and the Far East far more accessible by eliminating reliance on treacherous sea routes down the African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope and overland routes through the Middle East. Trans-continental rail through Canada and the U.S. in the late 1860s opened up North America to adventurous travelers. By the time Cook toured the world, local steamship and rail companies had filled the smaller gaps in his global route.

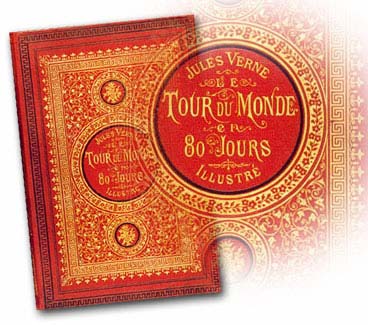

Cook’s first round-the-world journey sparked tremendous interest among the increasingly mobile populations of Europe and America. Sensing the potential of world tours, rival companies quickly developed their own routes. Competition soon stiffened: the Excursionist, a travel magazine published by Cook, took great pride in noting a failed French attempt to duplicate his journey in 1879. Cook’s journey is also thought to have inspired Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days.

Gilded cover of the French first edition of Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, published on January 30, 1873 (with an inset enlargement of the title).

[gj40040]

|

|

Verne completed the novel in December of 1872 while Cook was still en route, but Verne family records indicate he was inspired by a leaflet Cook had published to promote his trip. The popularity of Cook’s tours and Verne’s novel encouraged adventurers and enterprising journalists to complete the trip in the shortest possible time. Nellie Bly, a reporter on assignment for her employer, the New York World, was first to break the eighty-day benchmark fictionalized in Verne’s novel. She departed from Hoboken Pier on November 14, 1889 at 9:30 a.m. and returned—to much celebration—seventy-two days, six hours, eleven minutes, and fourteen seconds later. George Griffiths broke this record in 1894, completing the journey, which he booked entirely through Cook’s company, in sixty-five days.

Globetrotters in Japan

Although the term was not in common use at the time, the beginning of the globetrotter phenomenon in Japan can be dated to 1867 when the Pacific Mail and Steamship Company began offering regular service between San Francisco and Yokohama.

Felice Beato, one of the early pioneers of tourist photography in Japan, commemorated this event in a caption he paired with a panoramic photograph of Yokohama showing several ships in the harbor: “In January 1867, the first of splendid steamers belonging to the Pacific Mail Steam-ship Company made her appearance from San Francisco; as the Head Quarters of the Company in the East are at Yokohama, an additional guarantee is afforded for its future consequence.” Beato was referring to the voyage of the Colorado, the ship on which Cook’s group would later book passage for his first world tour in 1872.

|

Photograph of Yokohama harbor, with an enlargement (overlay)

of the many ships from abroad. By Felice Beato, ca. 1869.

[Collection of the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College. bjh45]

|

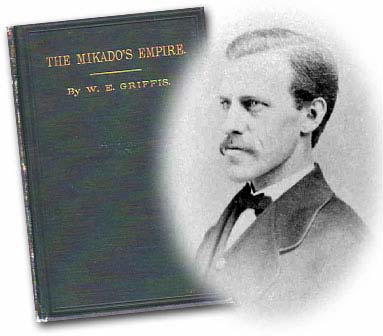

With regular trans-Pacific service bringing increasing numbers of tourists to Japan, long-term residents of the treaty ports began noting their presence with more frequency. Writing in The Mikado’s Empire, published in 1876 but based on his experiences from 1870 to 1874, William Elliot Griffis noted:

“The four great steamship agencies at present in Yokohama are the American Pacific Mail, the Oriental and Occidental; the English Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company; and the French Messageries Maratime Paquet Postes Francais. The Ocean Steamship Company has also an agency here. The native lines of mail steamers Mistu Bishi (Three Diamonds) also make Yokohama their terminus. The coming orthodox bridal tour and round-the-world trip will soon be made via Japan first, then Asia, Europe, and America.”

William Elliot Griffis and his book, The Mikado’s Empire, published 1876

[gj40044]

|

|

Griffis concludes this passage with the first use of the term globetrotters in a Japan-related publication. He refers to them as “circummundane tourists” and notes that they “have become so frequent and temporarily numerous in Yokohama as to be recognized as a distinct class. In the easy language of the port, they are called ‘globe-trotters.’”

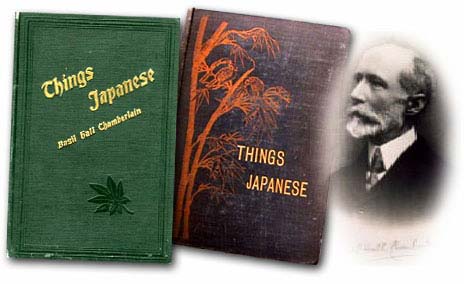

The behavior of globetrotters inspired much critical commentary wherever in the world they appeared, Japan included. Basil Hall Chamberlain, a highly influential scholar, included a tongue-in-cheek taxonomy of globetrotters in Things Japanese: Being Notes on Various Subjects Connected With Japan, first published in 1889 and reprinted in several later editions.

Basil Hall Chamberlain and several early editions of his book, Things Japanese, first edition published 1890 (right).

[gj40046]

|

|

His description, worth quoting in full for what it reveals of the attitudes toward globetrotters among long-term residents of Japan’s foreign community, was translated from Netto’s Papierschmetterlinge aus Japan, which Chamberlain describes as the “liveliest and best of all popular books on Japan.”

An excerpt about globetrotters follows.

|

Curt Netto (1847–1909) and his book Papierschmetterlinge aus Japan, which Chamberlain describes as the “liveliest and best of all popular books on Japan.” An excerpt about globetrotters follows.

|

Globe-trotter is the technical designation of a genus which, like the phylloxera and the Colorado beetle, had scarcely received any notice till recent times, but whose importance justifies us in devoting a few lines to it. It may be subdivided, for the most part, into the following species:

1. Globe-trotter communis. Sun-helmet, blue glasses, scant luggage, celluloid collars. His object is a maximum of traveling combined with a minimum of expense. He presents himself to you with some suspicious introduction or other, accepts with ill-dissembled glee your lukewarm invitation to him to stay, generally appears too late at meals, makes daily enquiries concerning jinrikisha fares, frequently invokes your help as interpreter to smooth over money difficulties between himself and the jinrikishamen, offers honest curio-dealers who have the entre to your house one-tenth of the price they ask, and loves to occupy your time, not indeed by gaining information from you about Japan (all that sort of thing he knows already much more thoroughly than you do), but by giving you information about India, China, and America, —places with which you are possibly as familiar as he. When the time for departure approaches, you must provide him with introductions even for places he has no present intention of visiting, but which he might visit. You will be kind enough, too, to have his purchases here packed up, —but, mind, very carefully. You will also see after freight and insurance, and dispatch the boxes to the address in Europe which he leaves with you. Furthermore, you will no doubt not mind purchasing and seeing to the packing of a few sundries which he himself has not had time to look after.

2. Globe-trotter scientificus. Spectacles, microscope, a few dozen note-books, alcohol, arsenical acid, seines, butterfly nets, other nets. He travels for special scientific purposes, mostly natural-historical (if zoological, then woe betide you!). You have to escort him on all sorts of visits to Japanese officials, in order to procure admittance for him to collections, museums, and libraries. You have to invite him to meet Japanese savants of various degrees, and to serve as interpreter on each such occasion. You have to insinuate researches concerning ancient Chinese books, to discover and engage the services of translators, draughtsmen, flyers and stuffers of specimens. Your spare room gradually develops into a museum of natural history, a fact you can smell at the very threshold. In this case, too, the packing, passing through the custom-house, and dispatching of the collection falls to your lot; and happy are you if the objects arrive at home in a good state of preservation, and you have not to learn later on that such and such an oversight in packing has caused “irreparable” losses. Certain it is that, for years after, you will be reminded of your inquisitive guest by letters wherein he requests you to give him the details of some scientific specialty whose domain is disagreeably distant from your own, or to procure for him some creature or other which is said to have been observed in Japan at some former period.

3. Globe-trotter elegans. Is provided with good introductions from his government, generally stops at a legation, is interested in shooting, and allows the various charms of the country to induce him to prolong his stay.

4. Globe-trotter independens. Travels in a steam-yacht, generally accompanied by his family. Chief goal of his journey: an audience with the Mikado.

5. Globe-trotter princeps. Princes or other dignitaries recognizable by their numerous suite, and who undertake the round journey (mostly on a man of war) either for political reasons or for the purposes of self-instruction. This species is useful to foreign residents, in so far as the receptions and fetes given in their honour create an agreeable diversion.

We might complete our collection by the description of a few other species, eg., the Globe-trotter desperatus, who expends his utmost farthing on a ticket to Japan with the hope of making a fortune there, but who, finding no situation, has last to be carted home by some cheap opportunity at the expense of his fellow-countrymen. Furthermore might be noticed the Globe-trotter dolosus, who travels under some high-sounding name and with doubtful banking account, merely in order to put as great a distance as possible between himself and the home police. Likewise the Globe-trotter-locustus, the species that travels in swarms, perpetually dragged around the universe by Cook and the likes of Cook … Last, but not least, just a word for the Globe-trotter amabilis, a species which is fortunately not wanting and which is always welcome. I mean old friends and the new, whose memory lives fresh in the minds of our small community, connected as it is with the recollection of happy hours spent together. Their own hearts will tell them that not they, but others, are pointed at in the foregoing—perhaps partly too harsh—description.

Chamberlain’s Things Japanese, arranged like an encyclopedia with topics listed alphabetically, included an entry titled “Books on Japan,” which describes and recommends several scholarly publications on Japanese history and culture. Griffis’ Mikado’s Empire, noted above, was highly praised as a reliable source. But Chamberlain also took this opportunity to comment on what he thought were poor or inaccurate sources. He dismissed novels as something “we have never been able to make up our mind to dip into.” Travel books, for which he noted that “there is literally no end to the making of them,” bore the brunt of his ire. He singled out one title in particular for special scrutiny: “Perhaps the most entertaining specimen of globe-trotting literature of another caliber is that much older book, Miss Margaretha Wepper’s North Star and Southern Cross. We do not wish to make any statement which cannot be verified, and therefore we will not say that the author is as mad as a March hare. Her idée fixe seems to have been that every foreign man in Yokohama and “Jeddo” mediated an assault on her. As for the Japanese, she dismisses them as ‘disgusting creatures.’” In later editions of Things Japanese, Chamberlain expanded his list of globetrotter publications to include Letters to the Times, 1892 written by Rudyard Kipling, which he described favorably as “the most graphic ever penned by a globetrotter, —but then what a globetrotter.” But Kipling was the exception; Chamberlain’s general disdain for travel books had sharpened considerably. He described them as “the ordinary low level of globe-trotting literature—twaddle enlivened by statistics at second hand.”

Criticisms aside, it is noteworthy that Chamberlain applies the term globetrotter retroactively to Wepper. Although her book was published in 1876, she visited Japan in the 1860s, well before the term globetrotter had entered common usage. For Griffis, Chamberlain, and other Westerners who resided in Japan for extended periods, the term globetrotters took on an expanded meaning. One need not be traveling around the world to be a globetrotter; shorter journeys to the Far East or even just Japan could qualify as globetrotting. More specifically, the term connoted a manner of travel—commercial tours—and the attitudes it engendered. It implied a superficial engagement with the places, people, and culture one encountered. “Globe-trotter locustus the species that travels in swarms, perpetually dragged around the universe by Cook, or the likes of Cook” sums up precisely what Chamberlain had in mind when he wrote disparagingly about the globetrotter phenomenon in Japan.

|