|

Although commercial artists rowed out in small boats to draw pictures of Perry’s fleet on the occasion of the first visit in July 1853, few had the opportunity to behold the commodore in person. This was due, in no little part, to Perry’s decision to enhance his authority by making himself as inaccessible as possible. Indeed, he remained so secluded prior to the formal presentation of the president’s letter that some Japanese, it is said, took to calling his cabin on the flagship “The Abode of the High and Mighty Mysteriousness.” |

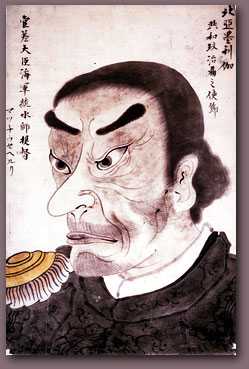

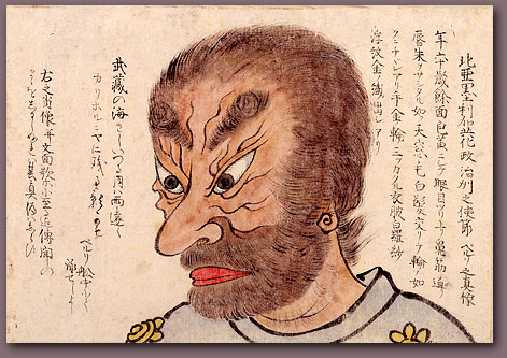

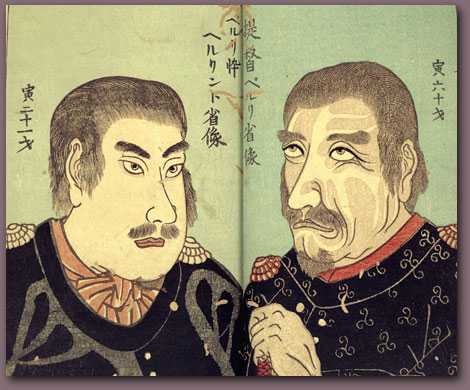

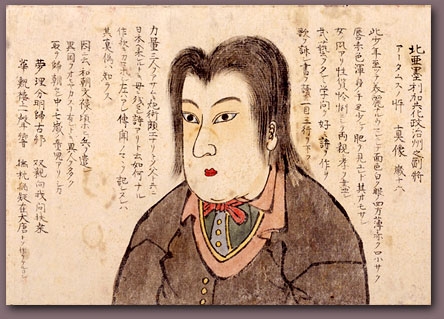

| The jowly, clean-shaven Perry captured in Mathew Brady’s famous photograph (left) is mirrored in the following woodblock prints from the time of his visit. |

|

|

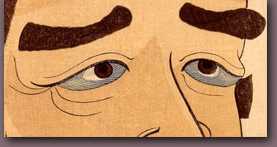

...but, amusingly, it is the whites of the Commodore’s eyes that are blue. | These portraits circulated with variations in detail and coloring. |

|

|

| The artwork in the Narrative begins with impressions of ports of call en route to Japan... |

We

can offer both a simple and a more subtle explanation for the startling

blue eyeballs in some of the Perry prints.

In feudal

Japan, Westerners were sometimes referred to as “blue-eyed barbarians,”

and it is possible that some artists were a bit confused about where

such blueness resided. It was also the case, however, that in Japanese

woodblock prints ferocious and threatening figures such as monsters

and renegades were stigmatized by the same strange blue eyeball. Whatever

the explanation, popular renderings of Perry and his fellow Americans

drew on conventions entrenched in Japanese culture. We

can offer both a simple and a more subtle explanation for the startling

blue eyeballs in some of the Perry prints.

In feudal

Japan, Westerners were sometimes referred to as “blue-eyed barbarians,”

and it is possible that some artists were a bit confused about where

such blueness resided. It was also the case, however, that in Japanese

woodblock prints ferocious and threatening figures such as monsters

and renegades were stigmatized by the same strange blue eyeball. Whatever

the explanation, popular renderings of Perry and his fellow Americans

drew on conventions entrenched in Japanese culture.

|

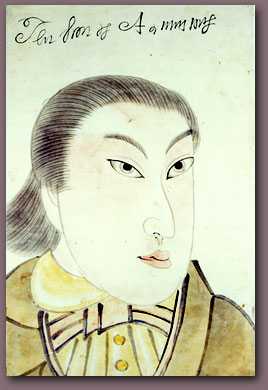

| One alarming close-up of Perry shows that appearances

can be deceiving. This ferocious image is accompanied by a poem, which

the commodore was imagined to have composed on board his flagship. Distant moon that appears over the Sea of Musashi, your beams also shine on California. Apparently, even barbarians might have Japanese-style poetic souls. |

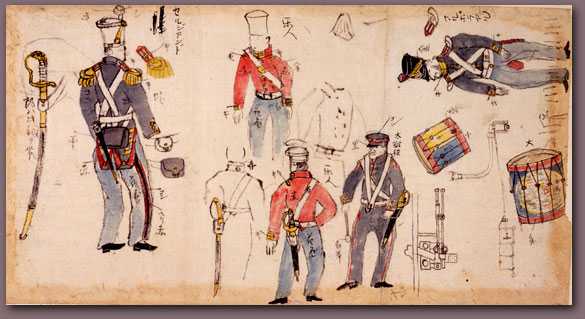

| Sketchbooks by Japanese artists reveal a thoughtful curiosity about the Americans. |

| This dramatic painting introduces a lively cast of characters. Colorful and idiosyncratic, they are a motley crew indeed. |

| Second-in Command Henry Adams’ 15-year-old son, who also accompanied the mission, was lavishly praised as delicate, aesthetic, muscular, martial, and a model of filial piety. |

| Navigator | Infantryman | Infantry Commander |

Crewman who surveys the depths |

Interpreter | Commodore Perry |

| Perry’s young son Oliver served as his personal secretary on the mission and appeared in a number of Japanese images. |

| Sailor from a “nation of black people” |

Musician | Marine |

| The most “realistic” run of portraits of the Americans dates from March 8, 1854, when Perry landed in Yokohama to initiate his second visit. Hibata Osuke, a well-known actor of Noh drama, managed to situate himself in the midst of that day’s activities and record a variety of subjects, including Perry and key figures who accompanied him. |

| Captain Joel Abbott | Perry’s son Oliver | Anton Portman, interpreter | S. Wells Williams, interpreter | Commander Henry Adams | Commodore Perry |

| Colored copies of Hibata’s sketches—like these

two sets of portraits—were made by anonymous artists who added their

unique touch. Click to view this set of portraits in the Encounters section |

| Here Oliver sports a trim mustache, but lacks the goatee which the artist imagined his father to have. |

| In this rendering, Oliver has been transformed into a delicate and romantic Japanese youth. |

Adams’

son, from the “Black Ship Scroll.” Adams’

son, from the “Black Ship Scroll.”Text: “This youth is extremely beautiful. His complexion is white, around his eyes is pink, his mouth is small, and his lips are red. His body, hands, and feet are slightly plump, and his features are rather feminine. He is intelligent by nature, dutiful to his parents, and has a taste for the martial arts. He likes scholarship, composes and recites poems and songs, and reads books three lines at a glance. His power exceeds three men, and his shooting ability is exceptional...” |

|

Portrait of Perry, photograph by Mathew B. Brady, ca. 1856, Library of

Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Portrait of Perry, a North American, ca. 1854, woodblock print, © Nagasaki Prefecture. A Portrait of Perry, a North American, woodblock print, ca. 1854, courtesy Peabody Essex Museum. Images courtesy of Ryosenji Treasure Museum: A North American (Portrait of Perry), ca. 1854. Portrait of Matthew Perry, painting, ca. 1854. Portraits of Perry and Adams (detail), painting, 19th c. Black Ship Scroll, Perry detail © Honolulu Academy of Art. Back Ship and the Crew, painting, ca. 1854. Sketchbook for the Pictorial Description of Perry’s Visit, ca. 1853, © Tokyo University Historiographical Institute. Two colored renderings based on Hibata Osuke’s 1854 sketches of Perry and five others: Chrysler Museum of Art (above), and Shiryo Hensanjo, University of Tokyo (above right) Perry and son, woodblock print, 1854, Ryosenji Treasure Museum Perry’s son Oliver, painting, ca. 1854, Ryosenji Treasure Museum Adams’ son, detail from the 1854 “Black Ship Scroll,” Honolulu Academy of Art On viewing images from the historical record: click here. Black Ships & Samurai © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology A project of professors John W. Dower & Shigeru Miyagawa Design and production by Ellen Sebring, Scott Shunk, and Andrew Burstein |