| |

|

Perry,

ca. 1854 Perry,

ca. 1854 |

Perry, ca. 1856

|

|

©

Nagasaki Prefecture ©

Nagasaki Prefecture

|

by Mathew Brady,

Library of Congress |

On

July 8, 1853, residents of Uraga on the outskirts of Edo, the sprawling

capital of feudal Japan, beheld an astonishing sight. Four foreign

warships had entered their harbor under a cloud of black smoke, not

a sail visible among them. They were, startled observers quickly learned,

two coal-burning steamships towing two sloops under the command of

a dour and imperious American. Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry had

arrived to force the long-secluded country to open its doors to the

outside world. |

“The Spermacetti Whale”

by J. Stewart, 1837

New Bedford Whaling Museum

|

|

|

This

was a time that Americans can still picture today through Herman

Melville’s great novel Moby Dick,

published in 1851—a time when whale-oil lamps illuminated

homes, baleen whale bones gave women’s skirts their copious

form,

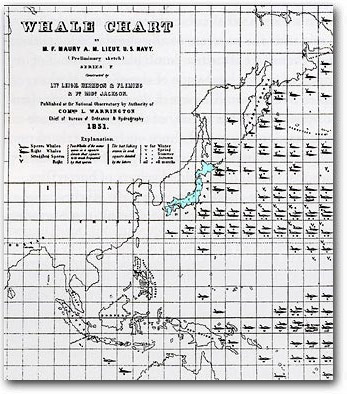

Whale

Chart, Japan in blue (detail, color added)

by M.F. Maury, US Navy, 1851

New Bedford Whaling Museum

|

and much industrial machinery was lubricated with the

leviathan’s oil. For several decades, whaling ships departing

from New England ports had plied the rich fishery around Japan,

particularly the waters near the northern island of Hokkaido.

They were prohibited from putting in to shore even temporarily

for supplies, however, and shipwrecked sailors who fell into

Japanese hands were commonly subjected to harsh treatment.

This situation could not last.

“If that double-bolted land, Japan, is ever to become

hospitable,” Melville wrote in Moby Dick, “it

is the whaleship alone to whom the credit will be due, for already

she is on the threshold.” One of the primary objectives

of Perry’s expedition was to demand that castaways be

treated humanely and whalers and other American vessels be provided

with one or two ports of call with access to “coal, provisions,

and water.”

The

message Perry brought to Japan’s leaders from President Millard

Fillmore also looked forward, in very general terms, to the eventual

establishment of mutually beneficial trade relations. On the surface,

Perry’s

President

Fillmore’s

1853 letter to

“The Emperor of Japan”

|

demands seemed relatively modest. Yet, as his own career

made clear, this was also a moment when the world stood on the cusp

of phenomenal change.

Nicknamed “Old Bruin” by one of his early crews (and “Old

Hog” and other disparaging epithets by crewman with the Japan

squadron), Matthew Perry was the younger brother of Oliver Hazard

Perry, hero of the American victory over the British on Lake Erie

in 1813. His own fame as a wartime leader had been established in

the recent U.S. war against Mexico, where he commanded a squadron

that raided various ports and supported the storming of Vera Cruz.

Victory over Mexico in 1848 did not merely add California to the United

States. It also opened the vista of new frontiers further west across

the Pacific Ocean. The markets and heathen souls of near-mythic “Asia” now beckoned more enticingly than ever before. Mars, Mammon, and God

traveled hand-in-hand in this dawning age of technological and commercial

revolution.

U.S. merchant firms had been involved in the China trade centering

on Canton since the previous century. Indeed, “Chinoiserie”—elegant

furnishings and objects d’art imported from the Far East, or

else mimicking Chinese and Japanese art and artifacts—graced

many fashionable European and American homes from the late-17th century

on. Following England’s victory in the Opium War of 1839-1842,

the United States joined the system of “unequal treaties”

that opened additional Chinese ports to foreign commerce. Tall, elegant

Yankee clipper ships engaged in a lively commerce that included not

merely Oriental luxuries such as silks, porcelains, and lacquer ware,

but also opium (for China) and Chinese coolies (to help build America’s

transcontinental railway). Now,

as Perry would ponderously convey to the Japanese, ports on the West

Coast such as San Francisco were opening up as well. In the new age

of steam-driven vessels, the distance between California and Japan

had been reduced to but 18 days. Calculations concerning space,

and time, and America’s “manifest destiny” itself

had all been dramatically transformed.

For Americans, Perry’s expedition to Japan was but one momentous

step in a seemingly inexorable westward expansion that ultimately spilled across the Pacific

to embrace the exotic “East.” For the Japanese, on the

other hand, the intrusion of Perry’s warships was traumatic,

confounding, fascinating, and ultimately devastating.

For almost a century prior to the 1630s, Japan had in fact engaged

in stimulating relations with European trading ships and Christian

missionaries. Widely known as the “southern barbarians” (since they arrived from the south, after sailing around India and

through the South Seas), these foreigners established a particularly

strong presence in and around the great port city of Nagasaki on the

southern island of Kyushu. Spain, Portugal, Holland, and England engaged

in a lucrative triangular trade involving China as well as Japan.

Protestant missionaries eventually followed their Catholic predecessors

and rivals, and by the early-17th century Christian converts in Kyushu

were calculated to number many tens of thousands. (Catholic missionaries put the figure at around a quarter

million.) At the same time, Japanese culture had become enriched by

a brilliant vogue of “Southern Barbarian” art—by

artwork, that is, that depicted the Europeans in Japan as well as

the lands and cultures from which they had come. This new world of

visual imagery ranged from large folding screens depicting the harbor

at Nagasaki peopled with foreigners and their trading ships to both

religious and secular paintings copied from European sources.

|

The arrival of “Southern Barbarians,” 17th-century folding screen

Nagasaki Prefecture

|

During these same decades, the Japanese themselves were venturing abroad. Their voyagers established footholds in Siam and the Philippines, for example, and a small delegation of Japanese Christians actually visited the Vatican. The country seemed poised to join in the great age of overseas expansion.

All this came to an abrupt end in 1639, when the ruling warrior government enforced a strict “closed country” (sakoku) policy: Japanese were forbidden to travel abroad, foreigners were expelled, and Christian worship was forbidden and cruelly punished. |

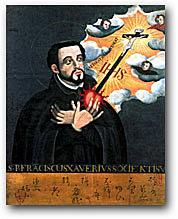

17th-century Japanese portrait of Francis

Xavier, the Spanish Jesuit who introduced Christianity to

Japan in the mid-16th century

Kobe City Museum

|

Fumie of Virgin Mary

with Christ child

Shiryo Hensanjo,

University of Tokyo

|

"Hidden Christians” reluctant to recant were ferreted out by forcing them to step on pictures or metal bas-reliefs of Christian icons such as the crucifixion or the Virgin Mary known as fumie (literally, “step-on pictures”), and observing their reactions—a practice the Japanese sometimes forced American castaways to do as well.

The rationale behind the draconian seclusion policy was both strategic and ideological. The foreign powers, not unreasonably, were seen as posing a potential military threat to Japan; and it was feared, again not unreasonably, that devotion to the Christian Lord might undermine absolute loyalty to the feudal lords who ruled the land.

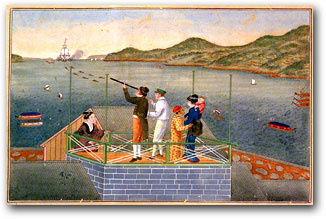

The most notable small exception to the seclusion policy was the continued presence of a Dutch mission confined to Dejima, a tiny, fan-shaped, artificial island in the harbor at Nagasaki. Through Dejima and the Dutch, the now isolated Japanese maintained a small window on developments in the outside world.

|

|

|

The “fan-shaped” island of

Dejima in Nagasaki harbor,

where the Dutch were

permitted to maintain

an enclave during

the period of seclusion

Nagasaki Prefecture (above left)

Peabody Essex Museum

|

|

|

Under

the seclusion policy, the Japanese enjoyed over two centuries of insular

security and economic self-sufficiency. Warriors became bureaucrats. Commerce flourished.

Major highways laced the land. Lively towns dotted the landscape,

and great cities came into being. At the time of Perry’s arrival,

Edo (later renamed Tokyo) had a population of around one million.

The very city that Perry’s tiny fleet approached in 1853 was

one of the greatest urban centers in the world—although the

outside world was unaware of this.

As it turned out, Perry himself never got to see Edo. Although his

mission to open Japan succeeded in every respect, the negotiations

took place in modest seaside locales. It remained for those who followed

to tell the world about Japan’s extraordinary capital city.

While the Japanese did not experience the political, scientific, and

industrial revolutions that were sweeping the Western world during

their two centuries of seclusion, these developments were not unknown

to them. Through the Dutch enclave at Dejima, a small number of Japanese

scholars had kept abreast of “Dutch studies” (Rangaku)

and “Western studies” (Yogaku). And as news of

European expansion filtered in, the feudal regime in Edo became alarmed

enough to relax its anti-foreign strictures and permit the establishment

of an official “Institute for the Investigation of Barbarian

Books.”

One of the earliest accounts of North America to appear in Japanese,

published in 1708, reflected more than a little confusion: it referred

to “a country cold and large…with many lions, elephants,

tigers, leopards, and brown and white bears,” in which “the

natives are pugnacious and love to fight.” As happens in secluded

societies everywhere, moreover, there existed a subculture of fabulous

stories about peoples inhabiting far-away places.

An 18th-century scroll titled “People of Forty-two Lands,”

for example, played to such imagination with illustrations of figures

with multiple arms and legs, people with huge holes running through

their upper bodies, semi-human creatures feathered head to toe like

birds, and so on.

|

|

“People

of Forty-two Lands” (details),

ca. 1720 “People

of Forty-two Lands” (details),

ca. 1720

Ryosenji Treasure Museum

|

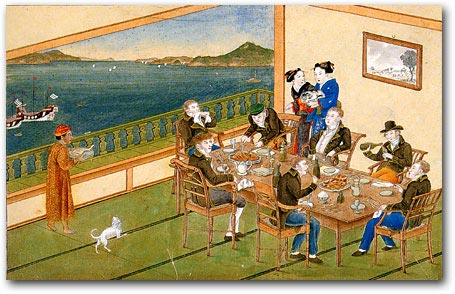

Such

grotesqueries belonged to a larger fantasy world of supernatural beings

that had countless visual representations in popular art. Throughout

the period of seclusion, however, naturalistic depictions of Europeans

in the tradition of the “Southern Barbarian” artwork continued

to be produced, particularly depicting the daily life of the “red

hairs,” as the Dutch in Dejima were commonly known.

|

Dutch dinner party

by Kawahara Keiga,

early-19th century

Peabody Essex Museum

|

|

|

Dutch family

by Jo Girin, ca. 1800

Peabody

Essex Museum

Dutch “surgery”

Kobe

City Museum

|

Concrete

knowledge of the West, including the United States, deepened over

time. The Japanese obtained Chinese translations of certain American

texts, including a standard history of the United States, and the

very eve of Perry’s arrival saw the publication of both a full-length

“New History of America” (which, among other things, singled

out egalitarianism, beef eating, and milk drinking) and a “General

Account of America” that described the Americans as educated

and civilized, and stated that they should be met “with respect

but not fear.”

|

|

Illustrations

from a Japanese book about the United States published on the eve

of Perry’s

arrival included imaginary renderings of “Columbus and Queen

Isabella” (left)

and “George Washington and Amerigo Vespucci” (!)

Collection of Carl H. Boehringer

|

The most vivid and intimate information available to Japanese officials

prior to Perry’s arrival came from “John Manjiro,”

a celebrated Japanese youth who had been shipwrecked while fishing

off the Japanese coast in 1841. Only 14 years old at the time,

John

Manjiro John

Manjiro

|

Manjiro was rescued by an American vessel and brought to the United

States. He lived in Fairhaven, Massachusetts for three years, sailed

for a while on an American whaler, and even briefly joined the gold

rush to California in 1849. When Manjiro finally made his way back

to Japan in 1851, samurai officials interrogated him at great length.

Manjiro praised the Americans as a people who were “upright

and generous, and do no evil”—although he noted that they

did engage in odd practices like reading in the toilet, living in

houses cluttered with furniture, and expressing affection between

men and women in public (in this regard, he found them “lewd”

and “wanton”). Manjiro also regaled his interrogators

with accounts of America’s remarkable technological progress,

including railways, steamships, and the telegraph. An account of his

adventures prepared with the help of a samurai scholar in 1852 even

included crude drawings of a paddle-wheel steamship and a train.

When Perry’s warships appeared off Uraga at the entry to Edo

Bay, they were thus not a complete surprise. The Dutch in Dejima had

informed the Japanese that the expedition was on its way. And John

Manjiro had already described the wonders of the steam engine. As

the official report of the Perry expedition later noted, “however

backward the Japanese themselves may be in practical science, the

best educated among them are tolerably well informed of its progress

among more civilized or rather cultivated nations.” Such abstract

knowledge, however, failed to mitigate the shock of the commodore’s

gunboat diplomacy.

Perry was not the first American to enter Japanese waters and attempt

to make that double-bolted land “hospitable.” Several

American vessels flying Dutch flags had entered Nagasaki harbor around the turn of the century, intent on commerce. In 1837,

the unarmed trading ship Morrison had approached Uraga on

a private mission to promote not only trade but also “the glory

of God in the salvation of thirty-five million souls.” At Uraga,

and again at Kagoshima on the southern tip of Kyushu, the vessel was

fired on and driven off. In 1845, the whaleship Manhattan

was allowed to briefly put in at Uraga to return 22 shipwrecked Japanese

sailors.

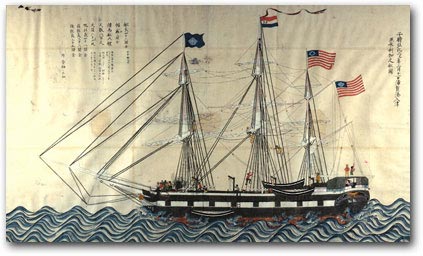

|

The

whaleship The

whaleship

Manhattan,

1845 watercolor by

an anonymous

Japanese artist

New Bedford

Whaling Museum |

|

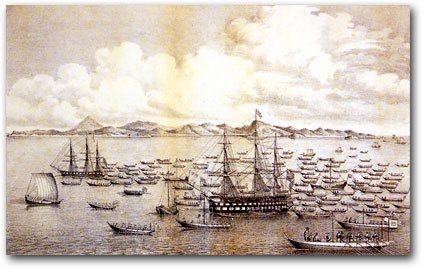

The

following year, two warships commanded by Commodore James Biddle entered

Edo Bay and engaged in preliminary contact with Japanese officials.

Biddle was not allowed to come ashore, however, and when ordered to

“depart immediately” did precisely as he had been told—leaving

no legacy beyond a few American and Japanese illustrations of his

warships.

|

|

Lithograph depicting Commodore Biddle’s

ships anchored in Edo Bay in 1846 and surrounded by small Japanese

boats

Peabody Essex Museum

|

Perry

possessed what his predecessors had lacked: grim determination, for

one thing—and, still more intimidating, the steam-driven warships. He was not to

be denied. And the erstwhile warrior leaders in Edo, who had not actually fought any wars for almost

two-and-a-half centuries, quickly recognized that they had no alternative

but to submit to his demands. They lacked the firepower—and

all the advanced technology such power exemplified—to resist.

Perry prepared diligently for his mission, and immersed himself in

the most authoritative foreign publications available on Japan. Some

of these accounts, emanating from Europeans who had been stationed

in Dejima, provided a general overview of political, economic, and

social conditions. An American geography text described Japan in flattering

terms as “the most civilized and refined nation of Asia,”

while other accounts, dwelling on the persecution of Christians and

inhospitable treatment meted out to castaways, spoke derisively of

a land that had regressed “into barbarism and idolatry.”

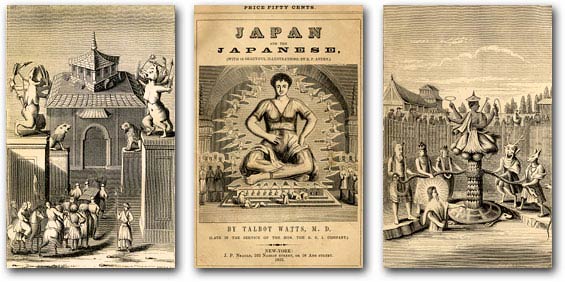

In Japan and the Japanese, a small book published in America

in 1852 as a send-off to the Perry expedition, a former employee of

the British East India Company paired synopses of prior writings with

a selection of illustrations that revealed how odd and exotic the

little-known heathen still remained in the imagination of Westerners. These thoroughly

fanciful graphics conjured up a world of bizarre religious icons commingled with sturdy

men and women wearing Chinese-style robes, holding large and stiff

fan-shaped implements, even promenading with folded umbrella-like

tents draped over their heads and carried from behind by an attendant.

|

|

Illustrations

in Japan and the Japanese (1852)

included the worshipping of idols,

“Habit of the Japanese Soldiers,” and “A Japanese

Lady of Quality”

|

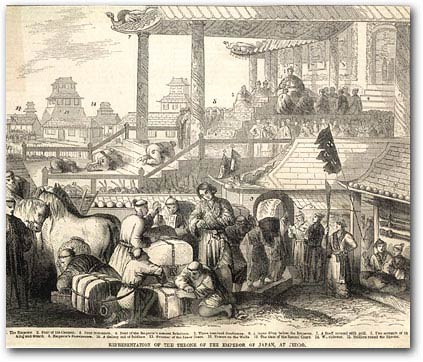

Such

fantasy masquerading as informed commentary and illustration was typical.

Just months before Perry’s arrival in Japan, the popular U.S.

periodical Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion

published a dramatic engraving depicting “the emperor of Japan”

holding public court in “Jeddo” (the old romanized spelling

of Edo, the capital city later renamed Tokyo). Here, too—despite

being annotated with fifteen numbered details—the graphic was

entirely imaginary. The emperor lived in Kyoto rather than Edo. His

palace surroundings were not highly Sinified (“Chinese”),

as depicted here. He never held public court. And Japanese “gentlemen”

and “soldiers” did not wear costumes or sport hairstyles

of the sort portrayed.

|

|

"Representation of the Throne of the Emperor of Japan, at Jeddo”

from the April 12, 1853 issue of

Gleason’s Pictorial

|

In his private journals, Perry himself anticipated encountering “a

weak and barbarous people,” and resolved to assume the most

forbidding demeanor possible within the bounds of proper decorum.

Despite his diligent preparations, he (much like Gleason’s

Pictorial) never fully grasped where real power resided and with

whom he was dealing. The letter he carried from President Fillmore

was addressed “To His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor of Japan,”

and the report the commodore published after his mission was completed

referred repeatedly to his dealings with “Imperial Commissioners.”

The hereditary imperial house in Kyoto was virtually powerless, however,

having ceded de facto authority some seven centuries previously to

warriors headed by a Shogun, or Supreme Commander. The “Imperial

Commissioners” to whom Perry conveyed his demands were actually

representatives of the warrior government headed by the Tokugawa clan,

which had held the position of Shogun since the beginning of the 17th

century.

In practice, none of this ambiguity mattered. Perry dealt with the

holders of real authority, and through them had his way.

His 1853 visit was short. While the Japanese looked on in horror,

the Americans blithely surveyed the waters around Edo Bay. On July

14, five days after appearing off Uraga, the commodore went ashore

with great pomp and ceremony to present his demands to the Shogun’s

officials, who had gathered onshore near what was then the little

town of Yokohama, south of Edo. Perry’s entourage of some 300

officers, marines, and musicians passed without incident through ranks

of armed samurai to a hastily erected “Audience Hall”

made of wood and cloth. There Perry handed over President Fillmore’s

letter, explained that the United States sought peace and prosperity

for both countries, and announced that he would return shortly, with

a larger squadron, for the government’s answer. Three days later,

the four American vessels weighed anchor and left.

Perry made good on his heavy-handed promise some six months later,

this time arriving in early March of 1854 with nine vessels (including

three steamers), over 100 mounted guns, and a crew of close to 1,800.

|

This second encounter was accompanied by far greater interaction and

socialization between the two sides. Gifts were exchanged, banquets

were held, entertainment was offered, and the Americans spent much

more time on shore, observing the countryside and intermingling with

ordinary Japanese as well as local officials. The high point of these

activities was a treaty signed on March 31 in Kanagawa, another locale

on Edo Bay, which met all of the U.S. government’s requests.

The Treaty of Kanagawa guaranteed good treatment of castaways, opened

two Japanese ports (Shimoda and Hakodate) for provisions and refuge,

and laid the groundwork for Japan’s reluctant acceptance of

an American “consul”—which, as soon transpired,

broke down the remaining barriers to Japan’s incorporation in

the global political economy.

The

Perry expeditions of 1853 and 1854 constitute an extraordinary moment

in the modern encounter between “East” and “West.”

Japan was suddenly “opened” to a world of foreign influences

and experiences that poured in like a flood and quickly seeped into

all corners of the archipelago. And the Americans—and other

foreigners who quickly followed on their heels (the British, Dutch,

French, and Russians)—abruptly found themselves face-to-face

with an “Oriental” culture that had hitherto existed primarily

as a figment of imagination. On all sides—whether facing “East”

or facing “West”—the experience was profound. Whole

new worlds became visualized in unprecedented ways.

|

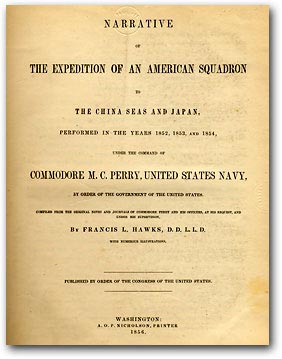

Title page of the official Narrative

of the Perry mission.

|

This

was true literally, not just figuratively. On the American side, Perry’s

entourage included two accomplished artists: William Heine and Eliphalet

Brown, Jr. Their graphic renderings— particularly Heine’s

detailed depictions of scenic sites and crowded activities—were

subsequently reproduced as tinted lithographs and plain woodcuts in

a massive official U.S. account of the expedition (published in three

volumes between 1856 and 1858, and cumbersomely titled Narrative

of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan,

performed in the years 1852, 1853, and 1854, under the Command of

Commodore M. C. Perry, United States Navy, by Order of the Government

of the United States). Additionally, a small selection of official

illustrations was made available in the form of large, independent,

brightly colored lithographs.

As

it happened, the Perry expeditions took place shortly after the invention

of daguerreotype photography (in 1839), and Eliphalet Brown, Jr. in

particular was entrusted with compiling a photographic record of the

mission. Although most of his plates were subsequently destroyed in

a fire, we still can easily imagine what was recorded through the

camera’s eye, for the official narrative also includes woodcuts

and lithographs of carefully posed Japanese that are explicitly identified

as being “from a daguerreotype.”

On the Japanese side, there was no comparable official visual record

of these encounters, although we know from accounts of the time that

boatloads of Japanese artists and illustrators rushed out to draw

the “black ships” from virtually the moment they appeared

off Uraga. What we have instead of a consolidated official collection

is a scattered treasury of graphic renderings of various aspects of

the startling foreign intrusion. The Americans were, of course, as

alien to the Japanese as the Japanese were, in their turn, to the

Americans. They were, depending on the viewer, strange, curious, fascinating,

attractive, lumpish, humorous, outlandish, and menacing—frequently

an untidy mixture of several of these traits.

Japanese artists, moreover, rendered their impressions through forms

of expression that differed from the lithographs, woodcuts, paintings,

and photographs that Europeans and Americans of the time relied on

in delineating the visual world. Vivacious woodblock prints, cruder

runs of black-and-white “kawaraban” broadsheets,

and drawings and brushwork in a conspicuously “Japanese” manner constituted the primary vehicles through which the great encounters

of 1853 and 1854 were conveyed to a wider audience in Japan. Some

of this artwork spilled over into the realm of caricature and cartoon.

The complementary but decidedly contrasting American and Japanese

images of the Perry mission and opening of Japan constitute a rare moment in the history

of “visualizing cultures.” This was, after all, an unusually

concentrated face-to-face encounter between a fundamentally white,

Christian, and expansionist “Western” nation and a reclusive

and hitherto all-but-unknown “Oriental” society. It was

also a moment during which each side produced hundreds of graphic

renderings not only of the alien foreigner, but of themselves as well.

It is tempting, and indeed fascinating, to ask which side was more

“realistic” in its renderings—but this really misses

the point. For it is only by seeing the visual record whole, in its

fullest possible range and variety, that we can grasp how complex

and multi-layered these interactions really were.

|

|

|